Following on from (but unrelated to) my post last week about feed tools we have two posts, one from Deepak Singh, and one from Neil Saunders, both talking about ‘friend feeds’ or ‘lifestreams’. The idea here is of aggregating all the content you are generating (or is being generated about you?) into one place. There are a couple of these about but the main ones seem to be Friendfeed and Profiliac. See Deepaks’s post (or indeed his Friendfeed) for details of the conversations that can come out of these type of things.

A (small) feeding frenzy – Cameron Neylon, Science in the Open – 10 March 2008

Half the links in that quote are dead. I wrote the post above seven years ago today, and it very much marked a beginning. Friendfeed went on to become the coffee house for a broad community of people interested in Open Science and became the place where, for me at least, many of the key discussions took place. Friendfeed was one of a number of examples of “life feed” services. The original intent was as an aggregation point for your online activity but the feed itself rapidly became the focus. Facebook in particular owes a debt to the user experience of Friendfeed. Facebook bought Friendfeed for the team in 2009 and rapidly started incorporating its ideas.

Yesterday Facebook announced they were going to shutter the service that they have to be fair kept going for many years now with no revenue source and no doubt declining user numbers. Of course those communities that remained are precisely the ones that most loved what the service offered. The truly shocking thing is that although nothing has been done to the interface or services that Friendfeed offers for five years it still remains a best in class experience. Louis Gray had some thoughts on what was different about Friendfeed. It remains, in my view, the best technical solution and user experience for enabling the kind of sharing that researchers actually want to do. I remember reading about Robert Scoble disliked the way that Friendfeed worked, and thinking “all those things are a plus for researchers…”. Twitter is ok, Facebook really not up to the job, Figshare doesn’t have the social features and all the other “facebooks for science” simply don’t have critical mass. Of course, neither did Friendfeed once everyone left either…but while there was a big community there we had a glimpse of what might be possible.

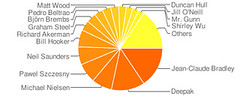

It’s also a reminder, as discussed in the Principles for Scholarly Infrastructures that Geoff Bilder, Jennifer Lin and myself released a week or so back, that relying on the largesse of third parties is not a reliable foundation to build on. If we want to take care of our assets as a community, we need to take responsibility for them as well. In my view there is some important history buried in the records of Friendfeed and I’m going to make some effort to build an archive. This script appears to do a good job of grabbing public feeds. It doesn’t pull discussions (ie the comments on other people’s posts) unless you have the “remote key” for that account. If anyone wants to send me their remote key (log in to friendfeed and navigate to http://friendfeed.com/remotekey) I’ll take a shot at grabbing their discussions as well. Otherwise I’ll just try and prioritize the most important accounts from my perspective to archive.

Is it recent history or is it ancient? We lost Jean-Claude Bradley last year, one of the original thinkers, and perhaps more importantly do-ers, of many strands in Open Research. Much of his thinking from 2008-2011 was on Friendfeed. For me, it was the space in which the foundations for a lot of my current thinking was laid. And where I met many of the people who helped me lay those foundations. And a lot of my insights into how technology does and does not help communities were formed by watching how much better Friendfeed was than many other services. Frankly a lot of the half-baked crap out there today could learn a lot by looking at how this nearly decade-old website works. And still works for those communities that have stayed in strength.

But that is the second lesson. It is the combination of functionality and the community that makes the experience so rich. My community, the Open Science group, left en masse after Facebook acquired Friendfeed. That community no longer trusted that the service would stay around (c.f. again those principles on trust). The librarian community stayed and had an additional five years of rich interactions. It’s hardly new to say that you need both community and technology working together to build a successful social media experience. But it still makes me sad to see it play out like this. And sad that the technology that demonstrably had the best user experience for research and scholarship in small(ish) communities never achieved the critical mass that it needed to succeed.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=37493daa-cc68-4a8d-8b63-ddde92d6ab8f)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=15257337-9d5a-4cdc-b515-65d448d0d26e)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=9ddf01df-59a5-4caf-954d-1bfa1f2691c8)