Next Tuesday I’m giving a talk at the Institute for Science Ethics and Innovation in Manchester. This is a departure for me in terms of talk subjects, in as much as it is much more to do with policy and politics. I have struggled quite a bit with it so this is an effort to work it out on “paper”. Warning, it’s rather long. The title of the talk is “Open Research: What can we do? What should we do? And is there any point?”

—

I’d like to start by explaining where I’m coming from. This involves explaining a bit about me. I live in Bath. I work at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, which is near Didcot. I work for STFC but this talk is a personal view so you shouldn’t take any of these views as representing STFC policy. Bath and Didcot are around 60 miles apart so each morning I get up pretty early, I get on a train, then I get on a bus which gets me to work. I work on developing methodology to study complex biological structures. We have a particular interest in trying to improve methods for looking at proteins that live in biological membranes and protein-nucleic acid complexes. I also have done work on protein labelling that lets us make cool stuff and pretty pictures. This work involves an interesting mixture of small scale lab work, work at large facilities on big instruments, often multi-national facilities. It also involves far too much travelling.

A good question to ask at this point is “Why?” Why do I do these things? Why does the government fund me to do them? Actually it’s not so much why the government funds them as why the public does. Why does the taxpayer support our work? Even that’s not really the right question because there is no public. We are the public. We are the taxpayer. So why do we as a community support science and research? Historically science was carried out by people sufficiently wealthy to fund it themselves, or in a small number of cases by people who could find wealth patrons. After the second world war there was a political and social concensus that science needed to be supported and that concensus has supported research funding more or less to the present day. But with the war receding in public memory we seem to have retained the need to frame the argument for research funding in terms of conflict or threat. The War on Cancer, the threat of climate change. Worse, we seem to have come to believe our own propaganda, that the only way to justify public research funding is that it will cure this, or save us from that. And the reality is that in most cases we will probably not deliver on this.

These are big issues and I don’t really have answers to a lot them but it seems to me that they are important questions to think about. So here are some of my ideas about how to tackle them from a variety of perspectives. First the personal.

A personal perspective on why and how I do research

My belief is we have to start with being honest with ourselves, personally, about why and how we do research. This sounds like some sort of self-help mantra I know but let me explain what I mean. My personal aim is to maximise my positive impact on the world, either through my own work or through enabling the work of others. I didn’t come at this from first principles but it has evolved. I also understand I am personally motivated by recognition and reward and that I am strongly, perhaps too strongly, motivated by others opinions of me. My understanding of my own skills and limitations means that I largely focus my research work on methodology development and enabling others. I can potentially have a bigger impact by building systems and capabilities that help others do their research than I can by doing that research myself. I am lucky enough to work in an organization that values that kind of contribution to the research effort.

Because I want my work to be used as far as is possible I make as much as possible of it freely available. Again I am lucky that I live now when the internet makes this kind of publishing possible. We have services that enable us to easily publish ideas, data, media, and process and I can push a wide variety of objects onto the web for people to use if they so wish. Even better than that I can work on developing tools and systems that help other people to do this effectively. If I can have a bigger impact by enabling other peoples research then I can multiply that again by helping other people to share that research. But here we start to run into problems. Publishing is easy. But sharing is not so easy. I can push to the web, but is anyone listening? And if they are, can they understand what I am saying?

A social perspective (and the technical issues that go with it)

If I want my publishing to be useful I need to make it available to people in a way they can make use of. We know that networks increase in value as they grow much more than linearly. If I want to maximise my impact, I have to make connections and maximise the ability of other people to make connections. Indeed Merton made the case for this in scientific research 20 years ago.

I propose the seeming paradox that in science, private property is established by having its substance freely given to others who might want to make use of it.

This is now a social problem but a social problem with a distinct technical edge to it. Actually we have two related problems. The issue of how I make my work available in a useful form and the separate but related issue of how I persuade others to make their work available for others to use.

The key to making my work useful is interoperability. This is at root a technical issue but at a purely technical level is one that has been solved. We can share through agreed data formats and vocabularies. The challenges we face in actually making it happen are less technical problems than social ons but I will defer those for the moment. We also need legal interoperability. Science Commons amongst others has focused very hard on this question and I don’t want to discuss it in detail here except to say that I agree with the position that Science Commons takes; that if you want to maximise the ability of others to re-use your work then you must make it available with liberal licences that do not limit fields of use or the choice of license on derivative works. This mean CC-BY, BSD etc. but if you want to be sure then your best choice is explicit dedication to the public domain.

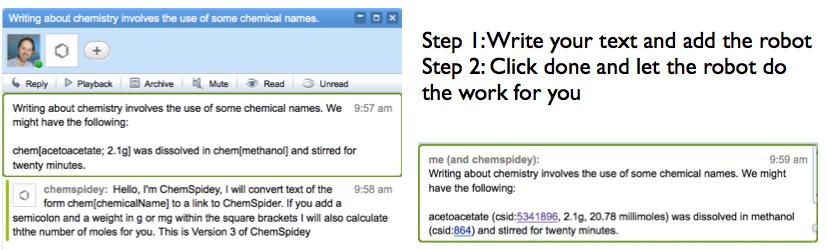

But technical and legal interoperability are just subsets of what I think is more important;Â process interoperability. If the object we publish are to be useful then they must be able to fit into the processes that researchers actually use. As we move to the question of persuading others to share and build the network this becomes even more important. We are asking people to change the way they do things, to raise their standards perhaps. So we need to make sure that this is as easy as possible and fits into their existing workflows. The problem with understanding how to achieve technical and legal interoperability is that the temptation is to impose it and I am as guilty of this as anyone. What I’d like to do is use a story from our work to illustrate an approach that I think can help us to make this easier.

Making life easier by capturing process as it happens: Objects first, structure later

Our own work on web based laboratory recording systems, which really originates in the group of Jeremy Frey at Southampton came out of earlier work on a fully semantic RDF backed system for recording synthetic chemistry. In contrast we took an almost completely unstructured approach to recording work in a molecular biology laboratory, not because we were clever or knew it would work out, but because it was a contrast to what had gone before. The LaBLog is based on a Blog framework and allows the user to put in completely free text, completely arbitrary file attachments, and to organize things in whichever way they like. Obviously a recipe for chaos.

And it was to start with as we found our way around but we went through several stages of re-organization and interface design over a period of about 18 months. The key realization we made was that while a lot of what we were doing was difficult to structure in advance that there were elements within that, specific processes, specific types of material that were consistently repeated, even stereotyped, and that structuring these gave big benefits. We developed a template system that made producing these repeated processes and materials much easier. These templates depended on how we organized our posts, and the metadata that described them, and the metadata in turn was driven by the need for the templates to be effective. A virtuous circle developed around the positive re-inforcement that the templates and associated metadata provided. More suprisingly the structure that evolved out of this matched in many cases well onto existing ontologies. In specific cases where it didn’t we could see that either the problem arose from the ontology itself, or the fact that our work simply wasn’t well mapped by that ontology. But the structure arose spontaneously out of a considered attempt to make the user/designer’s life easier. And was then mapped onto the external vocabularies.

I don’t want to suggest that our particular implementation is perfect. It is far from it, with gaping holes in the usability and our ability to actually exploit the structure that has developed. But I think the general point is useful. For the average scientist to be willing to publish more of their research, that process has to be made easy and it has to recognise the inherently unstructured nature of most research. We need to apply structured descriptions where they make the user’s life easier but allow unstructured or semi-structured representations elsewhere. But we need to build tools that make it easy to take those unstructured or semi-structure records and mold them into a specific structured narrative as part of a reporting process that the researcher has to do anyway. Writing a report, writing a paper. These things need to be done anyway and if we could build tools so that the easiest way to write the report or paper is to bring elements of the original record together and push those onto the web in agreed formats through easy to use filters and aggregators then we will have taken an enormous leap forward.

Once you’ve insinuated these systems into the researchers process then we can start talking about making that process better. But until then technical and legal interoperability are not enough – we need to interoperate with existing processes as well. If we could achieve this then much more research material would flow online, connections would be formed around those materials, and the network would build.

And finally – the political

This is all very well. With good tools and good process I can make it easier for people to use what I publish and I can make it easier for others to publish. This is great but it won’t make others want to publish. I believe that more rapid publication of research is a good thing. But if we are to have a rational discussion about whether this is true we need to have agreed goals. And that moves the discussion into the political sphere.

I asked earlier why it is that we do science as a society, why we fund it. As a research community I feel we have no coherent answer to these questions. I also talked about being honest to ourselves. We should be honest with other researchers about what motivates us, why we choose to do what we do, and how we choose to divide limited resources. And as recipients of taxpayers money we need to be clear with government and the wider community about what we can achieve. We also have an obligation to optimize the use of the money we spend. And to optimize the effective use of the outputs derived from that money.

We need at core a much more sophisticated conversation with the wider community about the benefits that research brings; to the economy, to health, to the environment, to education. And we need a much more rational conversation within the research community as to how those different forms of impact are and should be tensioned against each other. We need in short a complete overhaul if not a replacement of the post-war concensus on public funding of research. My fear is that without this the current funding squeeze will turn into a long term decline. And that without some serious self-examination the current self-indulgent bleating of the research community is unlikely to increase popular support for public research funding.

There are no simple answers to this but it seems clear to me that at a minimum we need to be demonstrating that we are serious about maximising the efficiency with which we spend public money. That means making sure that research outputs can be re-used, that wheels don’t need to re-invented, and innovation flows easily from the academic lab into the commercial arena. And it means distinguishing between the effective use of public money to address market failures and subsidising UK companies that are failing to make effective investments in research and development.

The capital generated by science is in ideas, capability, and people. You maximise the effective use of capital by making it easy to move, by reducing barriers to trade. In science we can achieve this by maximising the ability transfer research outputs. If we to be taken seriously as guardians of public money and to be seen as worthy of that responsibility our systems need to make ideas, data, methodology, and materials flow easily. That means making our data, our process, and our materials freely available and interoperable. That means open research.

We need a much greater engagement with the wider community on how science works and what science can do. The web provides an immense opportunity to engage the public in active research as demonstrated by efforts as diverse as Galaxy Zoo with 250,000 contributors and millions of galaxy classifications and the Open Dinosaur Project with people reading online papers and adding the measurements of thigh bones to an online spreadsheet. Without the publicly available Sloan Digital Sky Survey, without access to the paleontology papers, and without the tools to put the collected data online and share them these people, this “public”, would be far less engaged. That means open research.

And finally we need to turn the tools of our research on ourselves. We need to critically analyse our own systems and processes for distributing resources, for communicating results, and for apportioning credit. We need to judge them against the value for money they offer to the taxpayer and where they are found wanting we need to adjust. In the modern networked world we need to do this in a transparent and honest manner. That means open research.

But even if we agree these things are necessary, or a general good, they are just policy. We already have policies which are largely ignored. Even when obliged to by journal publication policies or funder conditions researchers avoid, obfuscate, and block attempts to gain access to data, materials, and methdology. Researchers are humans too with the same needs to get ahead and to be recognized as anyone else. We need to find a way to map those personal needs, and those personal goals, onto the community’s need for more openness in research. As with the tooling we need to “bake in” the openness to our processes to make it the easiest way to get ahead. Policy can help with cultural change but we need an environment in which open research is the simplest and easiest approach to take. This is interoperability again but in this case the policy and process has to interoperate with the real world. Something that is often a bit of a problem.

So in conclusion…

I started with a title I’ve barely touched on. But I hope with some of the ideas I’ve explored we are in a position to answer the questions I posed. What can we do in terms of Open Research? The web makes it technically possible for us the share data, process, and records in real time. It makes it easier for us to share materials though I haven’t really touched on that. We have the technical ability to make that data useful through shared data formats and vocabularies. Many of the details are technically and socially challenging but we can share pretty much anything we choose to on a wide variety of timeframes.

What should we do? We should make that choice easier through the development of tools and interfaces that recognize that it is usually humans doing and recording the research and exploiting the ability of machines to structure that record when they are doing the work. These tools need to exploit structure where it is appropriate and allow freedom where it is not. We need tools to help us map our records onto structures as we decide how we want to present them. Most importantly we need to develop structures of resource distribution, communication, and recognition that encourage openness by making it the easiest approach to take. Encouragement may be all that’s required. The lesson from the web is that once network effects take hold they can take care of the rest.

But is there any point? Is all of this worth the effort? My answer, of course, is an unequivocal yes. More open research will be more effective, more efficient, and provide better value for the taxpayer’s money. But more importantly I believe it is the only credible way to negotiate a new concensus on the public funding of research. We need an honest conversation with government and the wider community about why research is valuable, what the outcomes are, and how the contribute to our society. We can’t do that if the majority cannot even see those outcomes. The wider community is more sophisticated that we give it credit for. And in many ways the research community is less sophisticated than we think. We are all “the public”. If we don’t trust the public to understand why and how we do research, if we don’t trust ourselves to communicate the excitement and importance of our work effectively, then I don’t see why we deserve to be trusted to spend that money.