Michael Nielsen asked me to answer some questions about practical approaches to Open Science. You can see my answers up on his blog.

P ≠NP and the future of peer review

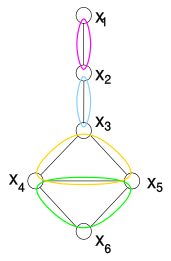

- Image via Wikipedia

“We demonstrate the separation of the complexity class NP from its subclass P. Throughout our proof, we observe that the ability to compute a property on structures in polynomial time is intimately related to the statistical notions of conditional independence and sufficient statistics. The presence of conditional independencies manifests in the form of economical parametrizations of the joint distribution of covariates. In order to apply this analysis to the space of solutions of random constraint satisfaction problems, we utilize and expand upon ideas from several fields spanning logic, statistics, graphical models, random ensembles, and statistical physics.”

Vinay Deolalikar [pdf]

No. I have no idea either, and the rest of the document just gets more confusing for a non-mathematician. Nonetheless the online maths community has lit up with excitement as this document, claiming to prove one of the major outstanding theorems in maths circulated. And in the process we are seeing online collaborative post publication peer review take off.

It has become easy to say that review of research after it has been published doesn’t work. Many examples have failed, or been partially successful. Most journals with commenting systems still get relatively few comments on the average paper. Open peer review tests have generally been judged a failure. And so we stick with traditional pre-publication peer review despite the lack of any credible evidence that it does anything except cost around a few billion pounds a year.

Yesterday, Bill Hooker, not exactly a nay-sayer when it comes to using the social web to make research more effective wrote:

“…when you get into “likes” etc, to me that’s post-publication review — in other words, a filter. I love the idea, but a glance at PLoS journals (and other experiments) will show that it hasn’t taken off: people just don’t interact with the research literature (yet?) in a way that makes social filtering effective.”

But actually the picture isn’t so negative. We are starting to see examples of post-publication peer review and see it radically out-perform traditional pre-publication peer review. The rapid demolition [1, 2, 3] of the JACS hydride oxidation paper last year (not least pointing out that the result wasn’t even novel) demonstrated the chemical blogosphere was more effective than peer review of one of the premiere chemistry journals. More recently 23andMe issued a detailed, and at least from an outside perspective devastating, peer review (with an attempt at replication!)Â of a widely reported Science paper describing the identification of genes associated with longevity. This followed detailed critiques from a number of online writers.

These, though were of published papers, demonstrating that a post-publication approach can work, but not showing it working for an “informally published” piece of research such as a a blog post or other online posting. In the case of this new mathematical proof, the author Vinay Deolalikar, apparently took the standard approach that one does in maths, sent a pre-print to a number of experts in the field for comments and criticisms. The paper is not in the ArXiv and was in fact made public by one of the email correspondents. The rumours then spread like wildfire, with widespread media reporting, and widespread online commentary.

Some of that commentary was expert and well informed. Firstly a series of posts appeared stating that the proof is “credible”. That is, that it was worth deeper consideration and the time of experts to look for holes. There appears a widespread skepticism that the proof will be correct, including a $200,000 bet from Scott Aaronson, but also a widespread view that it nonetheless is useful, that it will progress the field in a helpful way even if it is wrong.

After this first round, there have been summaries of the proof, and now the identification of potential issues is occurring (see RJLipton for a great summary). As far as I can tell these issues are potentially extremely subtle and will require the attention of the best domain experts to resolve. In a couple of cases these experts have already potentially “patched” the problem, adding their own expertise to contribute to the proof. And in the last couple of hours as Michael Nielsen pointed out to me there is the beginning of a more organised collaboration to check through the paper.

This is collaborative, and positive peer review, and it is happening at web scale. I suspect that there are relatively few experts in the area who aren’t spending some of their time on this problem this week. In the market for expert attention this proof is buying big, as it should be. An important problem is getting a good going over and being tested, possibly to destruction, in a much more efficient manner than could possibly be done by traditional peer review.

There are a number of objections to seeing this as a generalizable to other research problems and fields. Firstly, maths has a strong pre-publication communication and review structure which has been strengthened over the years by the success of the ArXiv. Moreover there is a culture of much higher standards of peer review in maths, review which can take years to complete. Both of these encourage circulation of drafts to a wider community than in most other disciplines, priming the community for distributed review to take place.

The other argument is that only high profile work will get this attention, only high profile work will get reviewed, at this level, possibly at all. Actually I think this is a good thing. Most papers are never cited, so why should they suck up the resource required to review them? Of those that are or aren’t published whether they are useful to someone, somewhere, is not something that can be determined by one or two reviewers. Whether they are useful to you is something that only you can decide. The only person competent to review which papers you should look at in detail is you. Sorry.

Many of us have argued for some time that post-publication peer review with little or no pre-publication review is the way forward. Many have argued against this on practical grounds that we simply can’t get it to happen, there is no motivation for people to review work that has already been published. What I think this proof, and the other stories of online review tell us is that these forms of review will grow of their own accord, particularly around work that is high profile. My hope is that this will start to create an ecosystem where this type of commenting and review is seen as valuable. That would be a more positive route than the other alternative, which seems to be a wholesale breakdown of the current system as the workloads rise too high and the willingness of people to contribute drops.

The argument always brought forward for peer review is that it improves papers. What interests me about the online activity around Deolalikar’s paper is that there is a positive attitude. By finding the problems, the proof can be improved, and new insights found, even if the overall claim is wrong. If we bring a positive attitude to making peer review work more effectively and efficiently then perhaps we can find a good route to improving the system for everyone.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Issues In The Proof That P≠NP (rjlipton.wordpress.com)

- Scott Aaronson adds $200K to prize money if P=NP proof correct (scottaaronson.com)

- HP Researcher Claims to Crack Compsci Complexity Conundrum (pcworld.com)

- S. Cook: “This appears to be a relatively serious claim to have solved P vs NP.” (gregbaker.ca)

- A Proof That P Is Not Equal To NP? (rjlipton.wordpress.com)

- R.J. Lipton – A proof that P is not equal to NP (rjlipton.wordpress.com)

- We need to fix peer review now (newscientist.com)

- Peer-review has a place (mndoci.com)

- Claimed Proof That P != NP (science.slashdot.org)

- Abundance Obsoletes Peer Review, so Drop It (opendotdotdot.blogspot.com)

- THE PROBLEM with peer review. “Especially for papers that rely on empirical work with painstakingly… (pajamasmedia.com)

The triumph of document layout and the demise of Google Wave

- Image via Wikipedia

I am frequently overly enamoured of the idea of where we might get to, forgetting that there are a lot of people still getting used to where we’ve been. I was forcibly reminded of this by Carole Goble on the weekend when I expressed a dislike of the Utopia PDF viewer that enables active figures and semantic markup of the PDFs of scientific papers. “Why can’t we just do this on the web?” I asked, and Carole pointed out the obvious, most people don’t read papers on the web. We know it’s a functionally better and simpler way to do it, but that improvement in functionality and simplicity is not immediately clear to, or in many cases even useable by, someone who is more comfortable with the printed page.

In my defence I never got to make the second part of the argument which is that with the new generation of tablet devices, lead by the iPad, there is a tremendous potential to build active, dynamic and (under the hood hidden from the user) semantically backed representations of papers that are both beautiful and functional. The technical means, and the design basis to suck people into web-based representations of research are falling into place and this is tremendously exciting.

However while the triumph of the iPad in the medium term may seem assured, my record on predicting the impact of technical innovations is not so good given the decision by Google to pull out of futher development of Wave primarily due to lack of uptake. Given that I was amongst the most bullish and positive of Wave advocates and yet I hadn’t managed to get onto the main site for perhaps a month or so, this cannot be terribly surprising but it is disappointing.

The reasons for lack of adoption have been well rehearsed in many places (see the Wikipedia page or Google News for criticisms). The interface was confusing, a lack of clarity as to what Wave is for, and simply the amount of user contribution required to build something useful. Nonetheless Wave remains for me an extremely exciting view of the possibilites. Above all it was the ability for users or communities to build dynamic functionality into documents and to make this part of the fabric of the web that was important to me. Indeed one of the most important criticisms for me was PT Sefton’s complaint that Wave didn’t leverage HTML formatting, that it was in a sense not a proper part of the document web ecosystem.

The key for me about the promise of Wave was its ability to interact with web based functionality, to be dynamic; fundamentally to treat a growing document as data and present that data in new and interesting ways. In the end this was probably just too abstruse a concept to grab hold of a user. While single demonstrations were easy to put together, building graphs, showing chemistry, marking up text, it was the bigger picture that this was generally possible that never made it through.

I think this is part of the bigger problem, similar to that we experience with trying to break people out of the PDF habit that we are conceptually stuck in a world of communicating through static documents. There is an almost obsessive need to control the layout and look of documents. This can become hilarious when you see TeX users complaining about having to use Word and Word users complaining about having to use TeX for fundamentally the same reason, that they feel a loss of control over the layout of their document. Documents that move, resize, or respond really seem to put people off. I notice this myself with badly laid out pages with dynamic sidebars that shift around, inducing a strange form of motion sickness.

There seems to be a higher aesthetic bar that needs to be reached for dynamic content, something that has been rarely achieved on the web until recently and virtually never in the presentation of scientific papers. While I philosophically disagree with Apple’s iron grip over their presentation ecosystem I have to admit that this has made it easier, if not quite yet automatic, to build beautiful, functional, and dynamic interfaces.

The rapid development of tablets that we can expect, as the rough and ready, but more flexible and open platforms do battle with the closed but elegant and safe environment provided by the iPad, offer real possibilities that we can overcome this psychological hurdle. Does this mean that we might finally see the end of the hegemony of the static document, that we can finally consign the PDF to the dustbin of temporary fixes where it belongs? I’m not sure I want to stick my neck out quite so far again, quite so soon and say that this will happen, or offer a timeline. But I hope it does, and I hope it does soon.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Google Bails on Wave (wired.com)

- So Long, Wave, But You’ll Live On In Your Successors (webworkerdaily.com)

- Google Wave is dead! Long live Google Wave! (programmableweb.com)

- Google’s Departing Wave (cyberculturalist.com)

- Apathy kills Google’s new-age Wave (go.theregister.com)

The Nature of Science Blog Networks

- Image by cameronneylon via Flickr

I’ve been watching the reflection on the Science Blogs diaspora and the wider conversation on what next for the Science Blogosphere with some interest because I remain both hopeful and sceptical that someone somewhere is really going crack the problem of effectively using the social web for advancing science. I don’t really have anything to add to Bora’s masterful summary of the larger picture but I wanted to pick out something that was interesting to me and that I haven’t seen anyone else mention.

Much of the reflection has focussed around what ScienceBlogs, and indeed Nature Network is, or was, good for as a place to blog. Most have mentioned the importance of the platform in helping to get started and many have mentioned the crucial role that the linking from more prominent blogs played in getting them an audience. What I think no-one has noted is how much the world of online writing has changed since many of these people started blogging. There has been consolidation in the form of networks and the growth of the internet as a credible media platform with credible and well known writers. At the same time, the expectations of those writers, in terms of their ability to express themselves through multimedia, campaigns, widgets, and other services has outstripped the ability of those providing networks to keep up. I don’t think it’s an accident that many of the criticisms of ScienceBlogs seem to be similar to those of Nature Network when it comes to technical issues.

What strikes me is a distinct parallel between the networks and scientific journals (and indeed newspapers). One of the great attractions of the networks, even two or three years ago, was that the technical details of providing a good quality user experience were taken care of for you. The publication process was still technically a bit difficult for many people who just wanted to get on and write. Someone else was taking care of this for you. Equally the credibility provided by ScienceBlogs or the Nature name were and still are a big draw. The same way a journal provides credibility, the assumption that there is a process back there that is assuring quality in some way.

The world, and certainly the web, has moved on. The publication step is easy – as it is now much easier on the wider web. The key thing that remains is the link economy. Good writing on the web lives and dies by the links, the eyeballs that come to it, the expert attention that is brought there by trusted curators. Scientists still largely trust journals to apportion up their valuable attention, and people will still trust the front page of ScienceBlogs and others to deliver quality content. But what the web teaches us over and over again is that a single criterion for authority, to quality curation, to editing is not enough. In the same way that a journal’s impact factor cannot tell you anything about the quality of an individual paper, a blog collective or network doesn’t tell you anything much about an individual author, blog, or piece of writing.

The future of writing on the web will be more diverse, more federated, and more driven by trusted and selective editors and discoverers who will bring specific types of quality content into my attention stream. Those looking for “the next science blogging network” will be waiting a while because there won’t be one, at least not one that is successful. There will be consolidation, there will larger numbers of people writing for commercial media outlets, both old and new, but there won’t be a network because the network will the web. What there will be, somehow, sometime, and I hope soon will be a framework in which we can build social relationships that help us discover content of interest from any source, and that supports people to act as editors and curators to republish and aggregate that content in new and interesting ways. That won’t just change the way people blog about science, but will change the way people communicate, discover, critique, and actually do science.

Like Paulo Nuin said, the future of scientific blogging is what it has always been. It’s just writing. It’s always just been writing. That’s not the interesting bit. The interesting bit is that how we find what we want to read is changing radically…again. That’s where the next big thing is. If someone figures out please tell me. I promise I’ll link to you.

Title of this post is liberally borrowed from some of Richard Grant’s of which the most recent was the final push it took for me to actually write it.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Good-bye ScienceBlogs, and Thank You [The Primate Diaries] (scienceblogs.com)

- Who Will Read Your Excellent Science Blog Writing? (scienceblogs.com)

- Why Eric Johnson is leaving ScienceBlogs (andrewspittle.net)

- Bora leaves ScienceBlogs with superb history and analysis of science blogging (scienceblogs.com)

- #IOweBora, do you? [DrugMonkey] (scienceblogs.com)

- ScienceBlogs: What if… [Dot Physics] (scienceblogs.com)

Driving UK Research – Is copyright a help or a hindrance?

- Image via Wikipedia

The following is my contribution to a collection prepared by the British Library and released today at the Wellcome Trust, called “Driving UK Research. Is copyright a help or a hindrance?â€Â - Press Release – Document[pdf] – which is being released under a CC-BY-NC license. The British Library kindly allowed authors to retain copyright on their contributions so I am here releasing the text into the public domain via a CCZero waiver. I would also like to acknowledge the contribution of Chris Morrison in editing and improving the piece.

If I want to be confident that this text will be used to its full extent  I am going to have to republish it separately to this collection. Not because the collection uses  restrictive rights management or licences, it actually uses a relatively liberal copyright licence. No, the problem is copyright itself and the way it interacts with how we create knowledge in the 21st century.

Until recently we would use texts or data by reading, taking notes, making photocopies, and then writing down new insights. We would refer to the originals by citing them. A person making limited copies or taking notes (perhaps quoting the text) does not breach copyright because of the notion of “fair dealingâ€. Making copies of reasonable portions of a work is explicitly not a violation of copyright. If it were we wouldn’t be able to do any useful work at all.

Today, scholarship and research cannot effectively proceed via manual human processes. There is simply too much for us to handle. On the other hand we have excellent computer systems that can, to some extent at least, take these notes for us. Automated assistants that can read the text for us, that can do text mining, data aggregation and indexing allowing us to cope with the volume of information. As these tools improve we have an opportunity to radically increase the speed of the innovation cycle, using the human brain for what it is best at: insight and creative thinking; and using machines for what they are best at: indexing, checking, collecting.

The problem is that to do this those machines need to take a copy of the whole of the text and in doing so they trigger copyright. Even though the collection you are reading is released under a Creative Commons licence that allows non-commercial use, no-one can take a copy, find an interesting sentence, and then index it if they are going to make money. Google are not allowed to check what is here and index it for us.

Or perhaps they are. Perhaps this does come under “fair use†in the US. Or maybe it does, but not in the UK. What about Australia? Or Brazil? All with slightly different copyright law and a slightly different relationship between copyright and contract law. Even if current legal opinion says it is allowed a future court case could change that. The only way I can be sure that my text is available into the future is to give up the copyright altogether.

To build effectively on the scientific and cultural data being generated today we need computers. If a human were doing the job it would clearly be covered by fair dealing. What we need is a clear and explicit statement that machine based analysis for the purpose of indexing, mining, or collecting references is a fair dealing exception, even where a full copy is taken. There clearly need to be boundaries. The entire work should not be kept or distributed. As with existing fair dealing we could have guidelines on amounts kept or quoted: perhaps no more than 5% of a work. These could easily be developed and be compatible with existing fair dealing guidance.

We risk stifling the development of new tools, both commercial and academic, and new knowledge under the weight of a legal regime that was designed to cope with the printing press. At the same time a simple statement that this kind of analysis is fair dealing will provide certainty without damaging the interests of copyright holders or complicating copyright law. These new uses will ultimately bring more traffic, and perhaps more customers, to the primary documents. By taking the simple and easy step of making automated analysis an allowable fair dealing exception everyone wins.

It’s not information overload, nor is it filter failure: It’s a discovery deficit

- Image via Wikipedia

Clay Shirky’s famous soundbite has helped to focus on minds on the way information on the web needs to be tackled and a move towards managing the process of selecting and prioritising information. But in the research space I’m getting a sense that it is fuelling a focus on preventing publication in a way that is analogous to the conventional filtering process involved in peer reviewed publication.

Most recently this surfaced at Chronicle of Higher Education, to which there were many responses, Derek Lowe’s being one of the most thought out. But this is not isolated.

@JISC_RSC_YH:Â How can we provide access to online resources and maintain quality of content? Â #rscrc10 [twitter via@branwenhide]

Me: @branwenhide @JISC_RSC_YH isn’t the point of the web that we can decouple the issues of access and quality from each other? [twitter]

There is a widely held assumption that putting more research onto the web makes it harder to find the research you are looking for. Publishing more makes discovery easier.

The great strength of the web is that you can allow publication of anything at very low marginal cost without limiting the ability of people to find what they are interested in, at least in principle. Discovery mechanisms are good enough, while being a long way from perfect, to make it possible to mostly find what you’re looking for while avoiding what you’re not looking for. Search acts as a remarkable filter over the whole web through making discovery possible for large classes of problem. And high quality search algorithms depend on having a lot of data.

It is very easy to say there is too much academic literature – and I do. But the solution which seems to be becoming popular is to argue for an expansion of the traditional peer review process. To prevent stuff getting onto the web in the first place. This is misguided for two important reasons. Firstly it takes the highly inefficient and expensive process of manual curation and attempts to apply it to every piece of research output created. This doesn’t work today and won’t scale as the diversity and sheer number of research outputs increases tomorrow. Secondly it doesn’t take advantage of the nature of the web. They way to do this efficiently is to publish everything at the lowest cost possible, and then enhance the discoverability of work that you think is important. We don’t need publication filters, we need enhanced discovery engines. Publishing is cheap, curation is expensive whether it is applied to filtering or to markup and search enhancement.

Filtering before publication worked and was probably the most efficient place to apply the curation effort when the major bottleneck was publication. Value was extracted from the curation process of peer review by using it reduce the costs of layout, editing, and printing through simple printing less. But it created new costs, and invisible opportunity costs where a key piece of information was not made available. Today the major bottleneck is discovery. Of the 500 papers a week I could read, which ones should I read, and which ones just contain a single nugget of information which is all I need? In the Research Information Network study of costs of scholarly communication the largest component of publication creation and use cycle was peer review, followed by the cost of finding the articles to read which represented some 30% of total costs. On the web, the place to put in the curation effort is in enhancing discoverability, in providing me the tools that will identify what I need to read in detail, what I just need to scrape for data, and what I need to bookmark for my methods folder.

The problem we have in scholarly publishing is an insistence on applying this print paradigm publication filtering to the web alongside an unhealthy obsession with a publication form, the paper, which is almost designed to make discovery difficult. If I want to understand the whole argument of a paper I need to read it. But if I just want one figure, one number, the details of the methodology then I don’t need to read it, but I still need to be able to find it, and to do so efficiently, and at the right time.

Currently scholarly publishers vie for the position of biggest barrier to communication. The stronger the filter the higher the notional quality. But being a pure filter play doesn’t add value because the costs of publication are now low. The value lies in presenting, enhancing, curating the material that is published. If publishers instead vied to identify, markup, and make it easy for the right people to find the right information they would be working with the natural flow of the web. Make it easy for me to find the piece of information, feature work that is particularly interesting or important, re-intepret it so I can understand it coming from a different field, preserve it so that when a technique becomes useful in 20 years the right people can find it. The brand differentiator then becomes which articles you choose to enhance, what kind of markup you do, and how well you do it.

All of these are things that publishers already do. And they are services that authors and readers will be willing to pay for. But at the moment the whole business and marketing model is built around filtering, and selling that filter. By impressing people with how much you are throwing away. Trying to stop stuff getting onto the web is futile, inefficient, and expensive. Saving people time and money by helping them find stuff on the web is an established and successful business model both at scale, and in niche areas. Providing credible and respected quality measures is a viable business model.

We don’t need more filters or better filters in scholarly communications – we don’t need to block publication at all. Ever. What we need are tools for curation and annotation and re-integration of what is published. And a framework that enables discovery of the right thing at the right time. And the data that will help us to build these. The more data, the more reseach published, the better. Which is actually what Shirky was saying all along…

Related articles by Zemanta

- Academic publishing is archaic (daniel-lemire.com)

- too much research (text-patterns.thenewatlantis.com)

- Clay Shirky’s COGNITIVE SURPLUS: how the net lets us share and do more than ever (boingboing.net)

- Cups, Buckets, Pools, and Puddles: When the Flood of Papers Won’t Abate, Which Do You Choose? (scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org)

Capturing and connecting research objects: A pitch for @sciencehackday

Jon Eisen asked a question on Friendfeed last week that sparked a really interesting discussion of what an electronic research record should look like. The conversation is worth a look as it illustrates different perspectives and views on what is important. In particular I thought Jon’s statement of what he wanted was very interesting:

I want a system where people record EVERYTHING they are doing in their research with links to all data, analyses, output, etc [CN – my italics]. And I want access to it from anywhere. And I want to be able to search it intelligently. Dropbox won’t cut it.

This is interesting to me because it maps onto my own desires. Simple systems that make it very easy to capture digital research objects as they are created and easy-to-use tools that make it straightforward to connect these objects up. This is in many ways the complement of the Reseach Communication as Aggregation idea that I described previously. By collecting all the pieces and connecting them up correctly we create a Research Record as Aggregation, making it easy to wrap pieces of this up and connect them to communications. It also provides a route towards bridging the divide between research objects that are born digital and those that are physical objects that need to be represented by digital records.

Ok. So so much handwaving – what about building something? What about building something this weekend at ScienceHackDay? My idea is that we can use three pieces that have recently come together to build a demonstrator of how such a system might work. Firstly the DropBox API is now available (and I have a developer key). DropBox is a great tool that delivers on the promise of doing one thing well. It sits on your computer and synchronises directories with the cloud and any other device you put it on. Just works. This makes it a very useful entry point for the capture of digital research objects. So Step One:

Build a web service on the DropBox API that enables users (or instruments) to subscribe and captures new digital objects, creating an exposed feed of resources.

This will enable us to captures and surface research objects with users simply dropping files into directories on local computers. Using DropBox means these can be natively synchronised across multiple user computers which is nice. But then we need to connect these objects up, ideally in an automatic way. To do this we need a robust and general way of describing relationships between them. As part of the OREChem project, a collaboration between Cambridge, Southampton, Indiana, Penn State and Cornell Universities and PubChem, supported by Microsoft, Mark Borkum has developed an ontology that describes experiments (unfortunately there is nothing available on the web as yet – but I am promised there will be soon!). Nothing so new there, been done before. What is new here is that the OREChem vocabulary describes both plans and instances of carrying out those plans. It is very simple, essentially describing each part of a process as a “stage†which takes in inputs and emits outputs. The detailed description of these inputs and outputs is left for other vocabularies. The plan and the record can have a one to one correspondence but don’t need to. It is possible to ask whether a record satisfies a plan and alternately given evidence that a plan has been carried out that all the required inputs must have existed at some point.

Why does this matter? It matters because for a particular experiment we can describe a plan. For instance a UV-Vis spectrophotometer measurement requires a sample, a specific instrument, and emits a digital file, usually in a specific format. If our webservice above knows that a particular DropBox account is associated with a UV-Vis instrument and it sees a new file of the right type it knows that the plan of a UV-Vis measurement must have been carried out. It also knows which instrument was used (based on the DropBox account) and might know who it was who did the measurement (based on the specific folder the file appeared in). The web service is therefore able to infer that there must exist (or have existed) a sample. Knowing this it can attempt to discover a record of this sample from known resources, the public web, or even by emailing the user, asking them for it, and then creating a record for them.

A quick and dirty way of building a data model and linking it to objects on the web is to use Freebase and the Freebase API. This also has the advantage that we can leverage Freebase Gridworks to add records from spreadsheets (e.g. sample lists) into the same data model. So Step Two:

Implement OREChem experiment ontology in Freebase. Describe a small set of plans as examples of particular experimental procedures.

And then Step Three:

Expand the web service built in Step One to annotate digital research objects captured in Freebase and connect them to plans. Attempt to build in automatic discovery of inferred resources from known and unknown resources, and a system to failover to ask the user directly.

Freebase and DropBox may not be the best way to do this but both provide a documented API that could enable something to be lashed up quickly. I’m equally happy to be told that SugarSync, Open Calais, or Talis Connected Commons might be better ways to do this, especially if someone will be at ScienceHackDay with expertise in this. Demonstrating something like this could be extremely valuable as it would actually leverage semantic web technology to do something useful for researchers, linking their data into a wider web, while not actually bothering them with the details of angle brackets

Related articles by Zemanta

- Dropbox API Lets You Add Cloud Storage to Your Apps (webmonkey.com)

- Why the web of data needs to be social (cameronneylon.net)

- Preview: Freebase Gridworks (simonwillison.net)

- Update: CML, Chem4Word, CheTA, OREChem, Lensfield (wwmm.ch.cam.ac.uk)

The BMC 10th Anniversary Celebrations and Open Data Prize

- Image via Wikipedia

Last Thursday night I was privileged to be invited to the 10th anniversary celebrations for BioMedCentral and to help announce and give the first BMC Open Data Prize. Peter Murray-Rust has written about the night and the contribution of Vitek Tracz to the Open Access movement. Here I want to focus on the prize we gave, the rationale behind it, and the (difficult!) process we went through to select a winner.

Prizes motivate behaviour in researchers. There is no question that being able to put a prize down on your CV is a useful thing. I have long felt, originally following a suggestion from Jeremiah Faith, that a prize for Open Research would be a valuable motivator and publicity aid to support those who are making an effort. I was very happy therefore to be asked to help judge the prize, supported by Microsoft, to be awarded at the BMC celebration for the paper in a BMC journal that was an oustanding example of Open Data. Iain Hrynaszkiewicz and Matt Cockerill from BMC, Lee Dirks from Microsoft Research, along with myself, Rufus Pollock, John Wilbanks, and Peter Murray-Rust tried to select from a very strong list of contenders a shortlist and a prize winner.

Early on we decided to focus on papers that made data available rather than software frameworks or approaches that supported data availability. We really wanted to focus attention on conventional scientists in traditional disciplines that were going beyond the basic requirements. This meant in turn that a whole range of very important contributions from developers, policy experts, and others were left out. Particularly noteable examples were “Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach” and “The FANTOM web resource: from mammalian transcriptional landscape to its dynamic regulation“.

This still left a wide field of papers making significant amounts of data available. To cut down at this point we looked at the licences (or lack thereof) under which resources were being made available. Anything that wasn’t broadly speaking “open” was rejected at this point. This included code that wasn’t open source, data that was only available via a login, or that had non-commercial terms. None of the data provided was explicitly placed in the public domain, as recommended by Science Commons and the Panton Principles, but a reasonable amount was made available in an accessible form with no restrictions beyond a request for citation. This is an area where we expect best practice to improve and we see the prize as a way to achieve that. To be considered any external resource will have to be compliant ideally with all of Science Commons Protocols, the Open Knowledge Definition, and the Panton Principles. This means an explicit dedication of data to the public domain via PDDL or ccZero.

Much of the data that we looked at was provided in the form of Excel files. This is not ideal but in terms of accessibility it’s actually not so bad. While many of us might prefer XML, RDF, or at any rate CSV files the bottom line is that it is possible to open most Excel files with freely available open source software, which means the data is accessible to anyone. Note that “most” though. It is very easy to create Excel files that make data very hard to extract. Column headings are crucial (and were missing or difficult to understand in many cases) and merging and formatting cells is an absolute disaster. I don’t want to point to examples but a plea to those who are trying to make data available: if you must use Excel just put column headings and row headings. No merging, no formatting, no graphs. And ideally export it as CSV as well. It isn’t as pretty but useful data isn’t about being pretty. The figures and tables in your paper are for the human readers, for supplementary data to be useful it needs to be in a form that computers can easily access.

We finally reduced our shortlist to only about ten papers where we felt people had gone above and beyond the average. “Large-scale insertional mutagenesis of a coleopteran stored grain pest, the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum, identifies embryonic lethal mutations and enhancer traps” received particular plaudits for making not just data but the actual beetles available. “Assessment of methods and analysis of outcomes for comprehensive optimization of nucleofection” and “An Open Access Database of Genome-wide Association Results” were both well received as efforts to make a comprehensive data resource available.

In the end though we were required to pick just one winner. The winning paper got everyone’s attention right from the beginning as it came from an area of science not necessarily known for widespread data publication. It simply provided all of the pieces of information, almost without comment, in the form of clearly set out tables. They are in Excel and there are some issues with formatting and presentation, multiple sheets, inconsistent tabulation. It would have been nice to see more of the analysis code used as well. But what appealed most was that the data were simply provided above and beyond what appeared in the main figures as a natural part of the presentation and that the data were in a form that could be used beyond the specific study. So it was a great pleasure to present the prize to Yoosuk Lee on behalf of the authors of “Ecological and genetic relationships of the Forest-M form among chromosomal and molecular forms of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto“.

Many challenges remain, making this data discoverable, and improving the licensing and accessibility all round. Given that it is early days, we were impressed by the range of scientists making an effort to make data available. Next year we will hope to be much stricter on the requirements and we also hope to see many more nominations. In a sense for me, the message of the evening was that the debate on Open Access publishing is over, its only a question of where the balance ends up. Our challenge for the future is to move on and solve the problems of making data, process, and materials more available and accessible so as to drive more science.

Metrics of use: How to align researcher incentives with outcomes

- Image via Wikipedia

It has become reflexive in the Open Communities to talk about a need for “cultural change”. The obvious next step becomes to find strong and widely respected advocates of change, to evangelise to young researchers, and to hope for change to follow. Inevitably this process is slow, perhaps so slow as to be ineffective. So beyond the grassroots evangelism we move towards policy change as a top down mechanism for driving improved behaviour. If funders demand that data be open, that papers be accessible to the wider community, as a condition of funding then this will happen. The NIH mandate and the work of the Wellcome Trust on Open Access show that this can work, and indeed that mandates in some form are necessary to raise levels of compliance to acceptable levels.

But policy is a blunt instrument, and researchers being who they are don’t like to be pushed around. Passive aggressive responses from researchers are relatively ineffectual in the peer reviewed articles space. A paper is a paper. If its under the right licence then things will probably be ok and a specific licence is easy to mandate. Data though is a different fish. It is very easy to comply with a data availability mandate but provide that data in a form which is totally useless. Indeed it is rather hard work to provide it in a form that is useful. Data, software, reagents and materials, are incredibly diverse and it is difficult to make good policy that can be both effective and specific enough, as well as general enough to be useful. So beyond the policy mandate stick, which will only ever provide a minimum level of compliance, how do we motivate researchers to putting the effort into making their outputs available in a useful form? How do we encourage them to want to do the right thing? After all what we want to enable is re-use.

We need more sophisticated motivators than blunt policy instruments, so we arrive at metrics. Measuring the ouputs of researchers. There has been a wonderful animation illustrating a Daniel Pink talk doing the rounds in the past week. Well worth a look and important stuff but I think a naive application of it to researchers’ motivations would miss two important aspects. Firstly, money is never “off the table” in research. We are always to some extent limited by resources. Secondly the intrinsic motivators, the internal metrics that matter to researchers, are tightly tied to the metrics that are valued by their communities. In turn those metrics are tightly tied to resource allocation. Most researchers value their papers, the places they are published and the citations received, as measures of their value, because that’s what their community values. The system is highly leveraged towards rapid change, if and only if a research community starts to value a different set of metrics.

What might the metrics we would like to see look like? I would suggest that they should focus on what we want to see happen. We want return on the public investment, we want value for money, but above all we want to maximise the opportunity for research outputs to be used and to be useful. We want to optimise the usability and re-usability of research outputs and we want to encourage researchers to do that optimisation. Thus if our metrics are metrics of use we can drive behaviour in the right direction.

If we optimise for re-use then we automatically value access, and we automatically value the right licensing arrangements (or lack thereof). If we value and measure use then we optimise for the release of data in useful forms and for the release of open source research software. If we optimise for re-use, for discoverability, and for value add, then we can automatically tension the loss of access inherent in publishing in Nature or Science vs the enhanced discoverability and editorial contribution and put a real value on these aspects. We would stop arguing about whether tenure committees should value blogging and start asking how much those blogs were used by others to provide outreach, education, and research outcomes.

For this to work there would need to be mechanisms that automatically credit the use of a much wider range of outputs. We would need to cite software and data, would need to acknowledge the providers of metadata that enabled our search terms to find the right thing, and we would need to aggregate this information in a credible and transparent way. This is technically challenging, and technically interesting, but do-able. Many of the pieces are in place, and many of the community norms around giving credit and appropriate citation are in place, we’re just not too sure how to do it in many cases.

Equally this is a step back towards what the mother of all metrics, the Impact Factor was originally about. The IF was intended as a way of measuring the use of journals through counting citations, as a means of helping librarians to choose which journals to subscribe to. Article Level Metrics are in many ways the obvious return to this where we want to measure the outputs of specific researchers. The H-factor for all its weaknesses is a measure of re-use of outputs through formal citations. Influence and impact are already an important motivator at the policy level. Measuring use is actually a quite natural way to proceed. If we can get it right it might also provide the motivation we want to align researcher interests with the wider community and optimise access to research for both researchers and the public.

Related articles by Zemanta

- John Wilbanks on Science Commons, and generativity in science (ethanzuckerman.com)

Why the web of data needs to be social

- Image by cameronneylon via Flickr

If you’ve been around either myself or Deepak Singh you will almost certainly have heard the Jeff Jonas/Jon Udell soundbite: ‘Data finds data. Then people find people’. Jonas is referring to data management frameworks and knowledge discovery and Udell is referring to the power of integrated data to bring people together.

At some level Jonas’ vision (see his chapter[pdf] in Beautiful Data) is what the semantic web ought to enable, the automated discovery of data or objects based on common patterns or characteristics. Thus far in practical terms we have signally failed to make this a reality, particularly for research data and objects.

Udell’s angle (or rather, my interpretation of his overall stance) is more linked to the social web – the discovery of common contexts through shared data frameworks. These contexts might be social groups, as in conventional social networks, a particular interest or passion, or – in the case of Jon’s championing of the iCalendar standard –  a date and place as demonstrated by the  the elmcity project supporting calendar curation and aggregation. Shared context enables the making of new connection, the creation of new links. But still mainly links between people.

It’s not the scientists who are social; it’s the data – Neil Saunders

The naïve analysis of the success of consumer social networks and the weaknesses of science communication has lead to efforts that almost precisely invert the Jonas/Udell concept. In the case of most of these “Facebooks for Scientists†the idea is that people find people, and then they connect with data through those people.

My belief is that it is this approach that has led to the almost complete failure of these networks to gain traction. Services that place the object  research at the centre; the reference management and bookmarking services, to some extent Twitter and Friendfeed, appear to gain much more real scientific use because they mediate the interactions that researchers are interested in, those between themselves and research objects. Friendfeed in particular seems to support this discovery pattern. Objects of interest are brought into your stream, which then leads to discovery of the person behind them. I often use Citeulike in this mode. I find a paper of interest, identify the tags other people have used for it and the papers that share those tags. If these seems promising, I then might look at the library of the person, but I get to that person through the shared context of the research object, the paper, and the tags around that object.

Data, data everywhere, but not a lot of links – Simon Coles

A common complaint made of research data is that people don’t make it available. This is part of the problem but increasingly it is a smaller part. It is easy enough to put data up that many researchers are doing so, in supplementary data of journal articles, on personal websites, or on community or consumer sites. From a linked data perspective we ought to be having a field day with this, even if it represents only a small proportion of the total. However little of this data is easily discoverable and most of it is certainly not linked in any meaningful way.

A fundamental problem that I feel like I’ve been banging on about for years now is that dearth of well built tools for creating these links. Finally these tools are starting to appear with Freebase Gridworks being an early example. There is a good chance that it will become easier over time for people to create links as part of the process of making their own record. But the fundamental problems we always face, that this is hard work, and often unrewarded work, are limiting progress.

Data friends data…then knowledge becomes discoverable

Human interaction is unlikely to work at scale. We are going to need automated systems to wire the web of data together. The human process simply cannot keep up with the ongoing annotation and connection of data at the volumes that are being generated today. And we can’t afford not to if we want to optimize the opportunities of research to deliver useful outcomes.

When we think about social networks we always place people at their centre. But there is nothing to stop us replacing people with data or other research objects. Software that wants to find data, data that wants to find complementary or supportive data, or wants to find the right software to convert or analyze it. Instead of Farmville or Mafia Wars imagine useful tools that make these connections, negotiate content, and identify common context. As pointed out to me by Paul Walk this is very similar to what was envisioned in the 90s as the role of software agents. In this view the human research users are the poorly connected users on the outskirts of the web.

The point is that the hard part of creating linked data is making the links, not publishing the data. The semantic web has always suffered from the chicken and egg problem of a lack of user-friendly ways to generate RDF and few tools that could really use that RDF in exciting ways even if it did exist. I still can’t do a useful search on which restaurants in Bath will be open next Sunday. The reality is that the innards of this should be hidden from the user, the making of connections needs to be automated as far as possible, and as natural as possible when the user has to be involved. As easy as hitting that “like” button, or right clicking and adding a citation.

We have learnt a lot about the principles of when and how social networks work. If we can apply those lessons to the construction of open data management and discovery frameworks then we may stand some chance of actually making some of the original vision of the web work.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Facebook and the Open Graph: good for Linked Data? (blogs.talis.com)

- Freebase Gridworks: A power tool for data scrubbers ” Jon Udell (faganm.com)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=d8fea424-9fd4-40df-8e52-00e3e46a388b)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=37493daa-cc68-4a8d-8b63-ddde92d6ab8f)