I love Stephen Sondheim musicals. In particular I love the way he can build an ensemble piece in which there can be 10-20 people onstage, apparently singing, shouting, and speaking complete disconnected lines, which nonetheless build into a coherent whole. Into the Woods (1987) contains many brilliant examples of the thoughts, fears, and hopes of a whole group of people building into a coherent view and message (see the opening for a taste and links to other clips). Those who believe in the wisdom of crowds in its widest sense see a similar possibility in aggregating the chatter found on the web into coherent and accurate assessments of problems. Those who despair of the ignorance of the lowest common denominator see most Web2 projects as a waste of time. I sit somewhere in the middle – believing that with the right tools, a community of people who care about a problem and have some form of agreed standards of behavior and disputation can rapidly aggregate a well informed and considered view of a problem and what it’s solution might be.

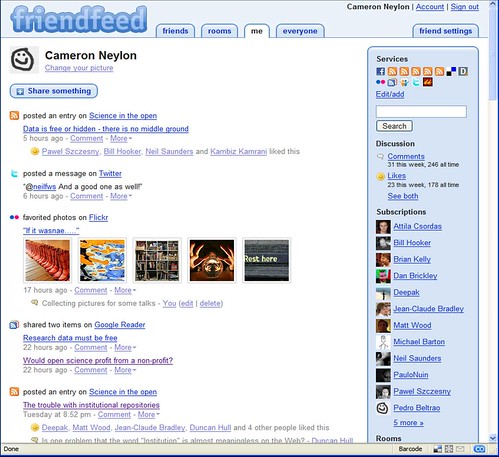

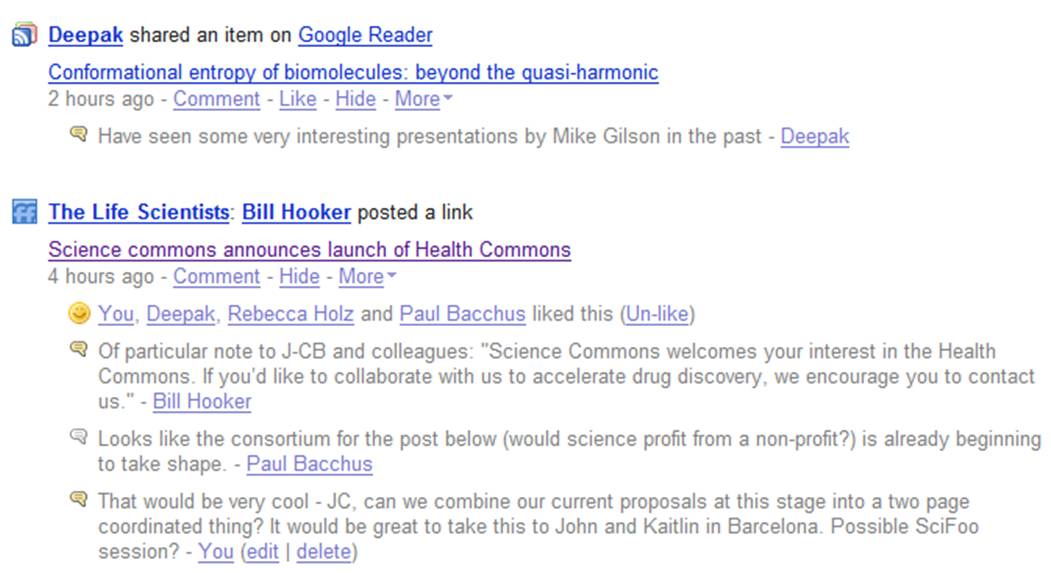

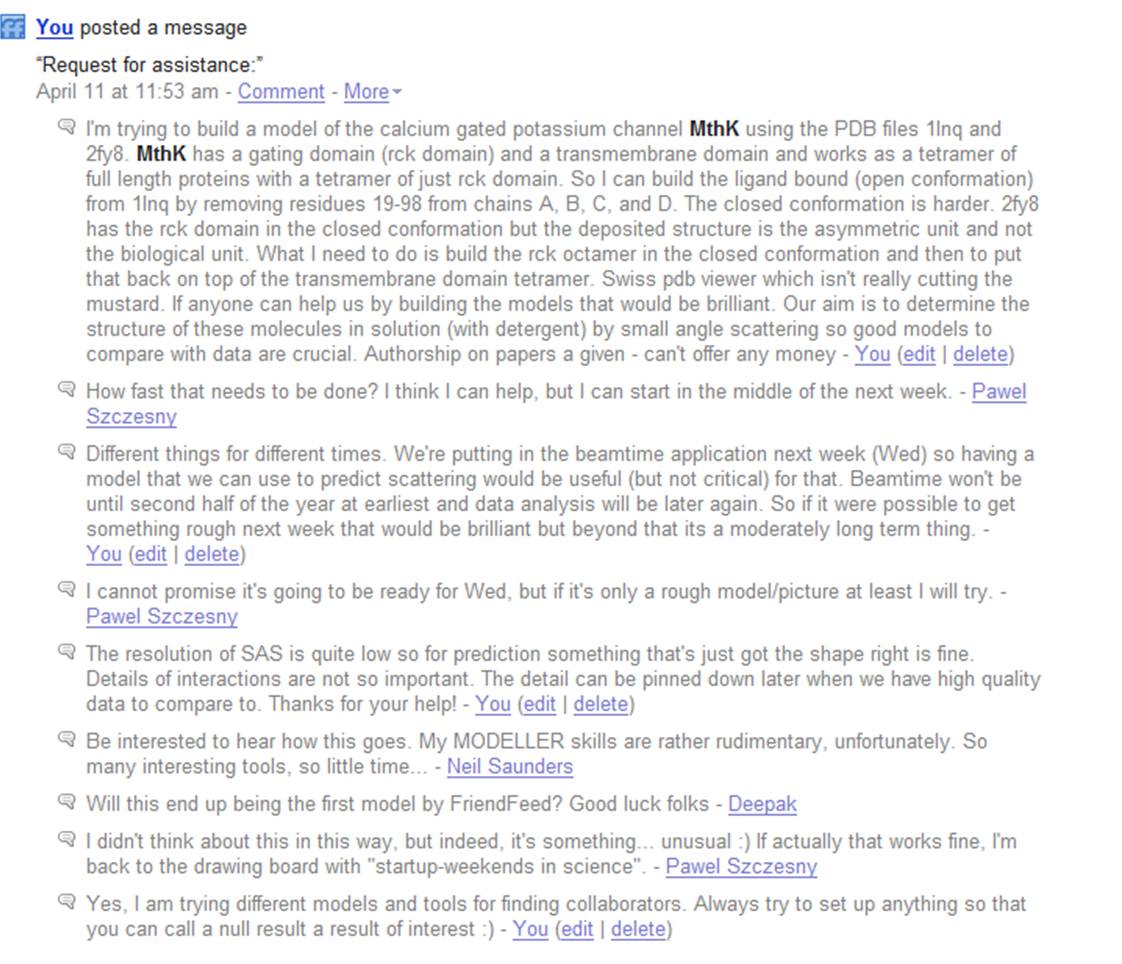

Yesterday and today, I saw one of the most compelling examples of that I’ve yet seen. Yesterday I posted a brain dump of what I had been thinking about following discussions in Hawaii and in North Carolina, about the possibilities of using OpenID to build a system for unique researcher IDs. The discussion on Friendfeed almost immediately aggregated a whole set of material, some of which I had not previously seen, proceded through a coherent discussion of many points, with a wide range of disparate views, towards some emerging conclusions. I’m not going to pre-judge those conclusions except to note there are some positions clearly developing that are contrary to my own view (e.g. on CrossRef being the preferred organisation to run such a service). This to me suggests the power of this approach for concensus building, even when that concensus is opposite to the position of the person kicking off the discussion.

What struck me with this was the powerful way in which Friendfeed rapidly enabled the conversation – and also the potential negative effect it had on widening the conversation beyond that community. Friendfeed is a very powerful tool for very rapidly widening the reach of a discussion like this one. It would be interesting to know how many people saw the item in their feeds. I could calculate it I suppose but for now I will just guess it was probably in the low to mid thousands. Many, many, more than subscribe to the blog anyway. What will be interesting to see is whether the slower process of blogospheric diffusion is informed by the Friendfeed discussion or runs completely independent of it (incidentally Friendfeed widget will hopefully be coming soon on the blog as well to try to and tie things together). Andy Powell of the Eduserv Foundation comments in his post of today that;

There’s a good deal of discussion about the post in Cameron’s FriendFeed. (It’s slightly annoying that the discussion is somewhat divorced from the original blog post but I guess that is one of the, err…, features of using FriendFeed?) [Andy also goes on to make some good point about delegation – CN]

The speed with which Friendfeed works, and the way in which it helps you build an interested community, and separated communities where appropriate, is indeed a feature of Friendfeed. Equally that speed and the fact that you need an account to comment, if not to watch, can be exclusionary. It is also somewhat closed off from the rest of the world. While I am greatly excited by what happened yesterday and today, indeed possibly just as excited as I am about yesterday’s other important news, it is important to make sure that the watering and care of the community doesn’t turn into the building of a walled garden.