Three things come together to make this post. The first is the paper The 2.5% Commitment by David Lewis, which argues essentially for top slicing a percentage off library budgets to pay for shared infrastructures. There is much that I agree with in the paper, the need for resourcing infrastructure, the need for mechanisms to share that burden, and fundamentally the need to think about scholarly communications expenditures as investments. But I found myself disagreeing with the mechanism. What motivates me to getting around to writing this is the recent publication of my own paper looking at resourcing of collective goods in scholarly communications, which lays out the background to my concerns, and the announcement from the European Commission that it will tender for the provision of a shared infrastructure for communicating research funded through Horizon2020 programs.

The problem of shared infrastructures

The challenge of resourcing and supporting infrastructure is well rehearsed elsewhere. We understand it is a collective action problem and that these are hard to solve. We know that the provision of collective and public-like goods is a problem that is not well addressed by markets, and better addressed by the state (for true public goods for which there are limited provisioning problems) or communities/groups (for collective goods that are partly excludable or rivalrous). One of the key shifts in my position has been the realization that knowledge (or its benefits) are not true public goods. They are better seen as club good or common pool resources for which we have a normative aspiration to make them more public but we can never truly achieve this.

This has important implications, chief amongst them that communities that understand and can work with knowledge products are better placed to support them than either the market, or the state. The role of the state (or the funder in our scholarly communications world) then becomes providing an environment that helps communities build these resources. It is the problem of which communities are best placed to do this that I discuss in my recent paper, focussing on questions of size, homogeneity, and solutions to the collective action problem drawing on the models of Mancur Olson in The Logic of Collective Action. The short version is that large groups will struggle, smaller groups, and in particular groups which are effectively smaller due to the dominance of a few players, will be better at solving these problems. Shorter version, publishers, of which there are really only 5-8 that matter will solve problems much better than universities, of which there are thousands.

Any proposal that starts “we’ll just get all the universities to do X” is basically doomed to failure from the start. Unless coordination mechanisms are built into the proposal. Mechanism one is abstract the problem up till there are a smaller number of players. ORCID is gaining institutional members in those countries where a national consortium has been formed. Particularly in Europe where a small number of countries have worked together to make this happen. The effective number of agents negotiating drops from thousands to around 10-20. The problem is this is politically infeasible in the United States where national coordination, government led is simply not possible. This isn’t incidentally an issue to do with Trump or Republicans but a long-standing reality in the USA. National level coordination, even between the national funding agencies is near impossible. The second mechanism is where a small number of players dominate the space. This works well for publishers (at least the big ones) although the thousands of tiny publishers do exploit the investment that the big ones make in shared infrastructures like Crossref. If the Ivy Plus group in the US did something, then maybe the rest would follow but in practice that seems unlikely. The patchwork of university associations is too disparate in most cases to reach agreement on sharing burden.

The final mechanism is one where there are direct benefits to contributors that arise as a side effect of contributing to the collective resource. More on that later.

A brief history of top-slicing proposals

The idea of top-slicing budgets to pay for scholarly infrastructure is not new. I first heard it explicitly proposed by Raym Crow in a meeting in the Netherlands that was seeking to find ways to fund OA Infrastructures. I have been involved in lobbying funders over many years that they need to do something along these lines. The Open Access Network follows a similar argument. The problem then, was the same as the problem now, what is the percentage? If I recall correctly Raym proposed 1%, others have suggested 1.5%, 2% and now 2.5%. Putting aside the inflation in the figure over the years there is a real problem here for any collective action. How can we justify the “correct” figure?

There are generally two approaches to this. One approach is to put a fence around a set of “core” activities and define the total cost of supporting them as a target figure. This approach has been taken by a group of biomedical funders convened by the Human Frontiers Science Program Organization who are developing a shared approach to funding to ensure “that core data resources for the life sciences should be supported through a coordinated international effort(s) that better ensure long-term sustainability and that appropriately align funding with scientific impact”. Important to note is that the convening involved a relatively small number of the most important funders, in a specific discipline, and it is a community organization, the ELIXR project that is working to define how “core data resources” should be defined. This approach has strengths, it helps define, and therefore build community through agreeing commitments to shared activities. It also has a weakness in that once that community definition is made it can be difficult to expand or generalize. The decisions of what is a “core data resource” in the biosciences is unlikely to map well to other disciplines for instance.

The second approach, attempts to get above the problem of disciplinary communities by defining some percentage of all expenditure to invest, effectively a tax on operations to support shared services. In many ways the purpose of the modern nation state is to connect such top-slicing, through taxation, to a shared identity and therefore an implicit and ongoing consent to the appropriation of those resources to support shared infrastructures that would otherwise not exist. That in turn is the problem in the scholarly communication space. Such shared identities and notions of consent do not exist. The somewhat unproductive argument over whether it is the libraries responsibility to cut subscriptions or academics responsibility to ask them to illustrates this. It is actually a shared responsibility, but one that is not supported by sense of shared identity and purpose, certainly not of shared governance. And notably success stories in cutting subscriptions all feature serious efforts to form and strengthen shared identity and purpose within an institution before taking action.

The problem lies in the politics of community. The first approach defines and delineates a community, precisely based on what it sees as core. While this strengthens support for those goods seen as core it can wall off opportunities to work with other communities, or make it difficult to expand (or indeed contract) without major ructions in the community. Top-slicing a percentage does two things, it presumes a much broader community with a sense of shared identity and a notion of consent to governance (which generally does not exist). This means that arguments over the percentage can be used as a proxy for arguments about what is in and out which will obscure the central issues of building a sense of community by debating the identity of what is in and out. In the absence of a shared identity it means adoptions requires unilateral action by the subgroup with their logistical hands on the budgets (in this case librarians). This is why percentages are favoured and those percentages look small. In essence the political goal is to hide this agenda in the noise. That makes good tactical sense, but leaves the strategic problem of building that shared sense of community that might lead to consent and consensus to grow ever bigger. It also stores up a bigger problem. It makes a shift towards shared infrastructures for larger proportions of the scholarly communications system impossible. The numbers might look big today, but they are a small part of managing an overall transition.

Investment returns to community as a model for internal incentives

Thus far you might take my argument as leading to a necessity for some kind of “coming together” for a broad consensus. But equally if you follow the line of my argument this is not practical. The politics of budgets within libraries are heterogeneous enough. Add into that the agendas and disparate views of academics across disciplines (not to mention ignorance on both sides of what those look like) and this falls into the category of collective action problems that I would describe as “run away from screaming”. That doesn’t mean that progress is not feasible though.

Look again at those cases where subscription cancellations have been successfully negotiated internally. These generally fall into two categories. Small(ish) institutions where a concerted effort has been made to build community internally in response to an internally recognized cash crisis, and consortial deals which are either small enough (see the Netherlands) or where institutions have bound themselves to act together voluntarily (see Germany, and to some extent Finland). In both cases community is being created and identity strengthened. In this element, I agree with Lewis’ paper, the idea of shared commitment is absolutely core. My disagreement is that I believe making that shared commitment an abstract percentage is the wrong approach. Firstly because any number will be arbitrary, but more importantly because it assumes common cause with academics that is not really there, rather than focusing on the easier task of building a community of action within libraries. This community can gradually draw in researchers, providing that it is attractive and sustainable, but to try and bridge this to start with is too big a gap to my mind.

This leads us to the third of Olson’s options for solving collective action problems. This option involves the generation of a byproduct, something which is an exclusive benefit to contributors, as part of the production of the collective good. I don’t think a flat percentage tax does this, but other financial models might. In particular reconfiguring the thinking of libraries around expenditure towards community investment might provide a route. What happens when we ask about return on investment to the scholarly community as a whole and to the funding library for not some percentage of the budget but the whole budget?

When we talk about about scholarly communications economics we usually focus on expenditure. How much money is going out of library or funder budgets? A question we don’t ask is how much of that money re-circulates within the community economy and how much leaves the system? To a first approximation all the money paid to privately held and shareholder owned commercial entities leaves the system. But this is not entirely true, the big commercials do invest in shared systems, infrastructure and standards. We don’t actually know how much, but there is at least some. You might think that non-profits are obliged to recirculate all the money but this is not true either, the American Chemical Society spends millions on salaries and lobbying. And so does PLOS (on salaries, not lobbying, ‘publishing operations’ is largely staff costs). For some of these organizations we have much better information on how much money is reinvested and how because of reporting requirements but it’s still limited.

You might think that two start-ups are both contributing similar value, whether they are (both) for profit or not-for-profit. But look closer, which ones are putting resources into the public domain as open access content, open source code, open data? How do those choices relate to quality of service? Here things get interesting. There’s a balance to found in investing in high quality services, which may be building on closed resources to secure a return to (someone else’s) capital, vs building the capital within the community. It’s perfectly legitimate for some proportion of our total budgets to leave the system, both as a route to securing investment from outside capital, but also because some elements of the system, particular user-facing service interfaces, have traditionally been better provided by markets. It also provides a playing field on which internal players might compete to make this change.

This is a community benefit but it also a direct benefit. Echoing the proposal of the Open Access Network, this investment would likely include instruments for investment in services (like Open Library of Humanities) and innovation (projects like Coko might be a good fit). Even if access to this capital is not exclusively accessible to projects affiliated with contributing libraries (which would be a legitimate approach, but probably a bit limiting) access to the governance of how that capital is allocated provides direct advantages to investing libraries. Access to the decisions that fund systems that their specific library needs is an exclusive benefit. Carefully configured this could also provide a route to draw in academics who want to innovate, as well as those who see the funding basis of their traditional systems crumbling. In the long term this couples direct benefits to the funding libraries to community building within the academic library community, to a long game of drawing in academics (and funders!) to an ecosystem in which their participation implies the consent of the governed, ultimately justifying a regime of appropriate taxation.

Actually in the end my proposal is not very different to Lewis’s. Libraries make a commitment to engage in and publicly report on their investment in services and infrastructure, in particular they report on how that portfolio provides investment returns to the community. There is competition for the prestige of doing better, and early contributors get to claim that prestige of being progressive and innovative. As the common investment pool grows there are more direct financial interests that bring more players in, until in the long term it may become an effectively compulsory part of the way academic libraries function. The big difference for me is not setting a fixed figure. Maybe setting targets would help, but in the first instance I suspect that simply reporting on community return on investment would change practice. One of the things Buchannan and Olson don’t address (or at least not to any great extent) is that identity and prestige are club goods. It is entirely economically rational for a library to invest in something that provides no concrete or immediate material return, if in doing so it gains profile and prestige, bolstering its identity as “progressive” or “innovative” in a way that plays well to internal institutional politics, and therefore in turn to donors and funders. Again, here I agree with Lewis and the 2.5% paper that signalling (including costly signalling from an evolutionary perspective) is a powerful motivator. Where I disagree is with the specifics of the signal, who it signals to, and how that can build community from a small start.

The inequity of traditional tenders

How does all of this relate to the European Commission statement that they will tender for an Open Science Platform? The key here is the terms of the tender. There is an assumption amongst many people I follow that F1000Research have this basically sewn up. Certainly based on numbers I’m aware of they are likely the best placed to offer a cost effective service that is also high quality. The fact that Wellcome, Gates and the African Academy of Sciences have all bought into this offering is not an accident. The information note states that the “Commission is implementing this action through a public procurement procedure, which a cost-benefit analysis has shown to be the most effective and transparent tool”. What the information note does not say is that the production of community owned resources and platforms will be part of the criteria. Framing this as an exercise in procuring a service could give very different results to framing it as investment in community resources.

Such tender processes put community organisations at a disadvantage. Commercial organisations have access to capital that community groups often do not. Community groups are more restricted in risk taking. But they are also more motivated, often it is part of their mission, to produce community resources, open source platforms and systems, open data, as well as the open content which is the focus of the Commission’s thinking. We should not exclude commercial and non-community players from competing for these tenders, far from it. They may well be more efficient, or provide better services. But this should be tensioned against the resources created and made available as as result of the investment. Particularly for the Commission, with its goal of systemic change, that question should be central. The resources that are offered to the community as part of a tender should have a value placed on them, and that should be considered in the context of pricing. The Commission needs to consider the quality of the investment it is making, as well as the price that it pays.

The key point of agreement, assessing investment quality

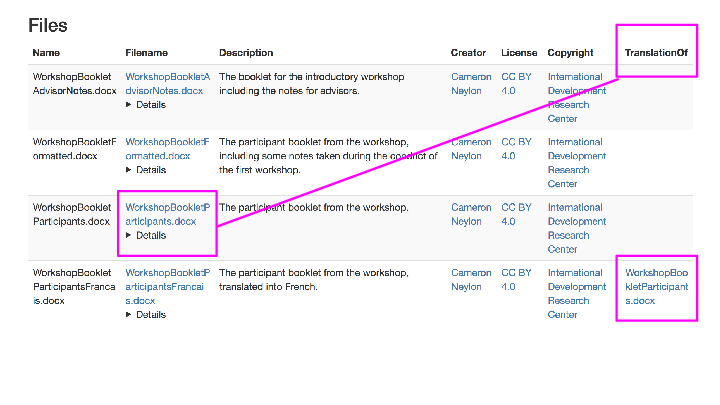

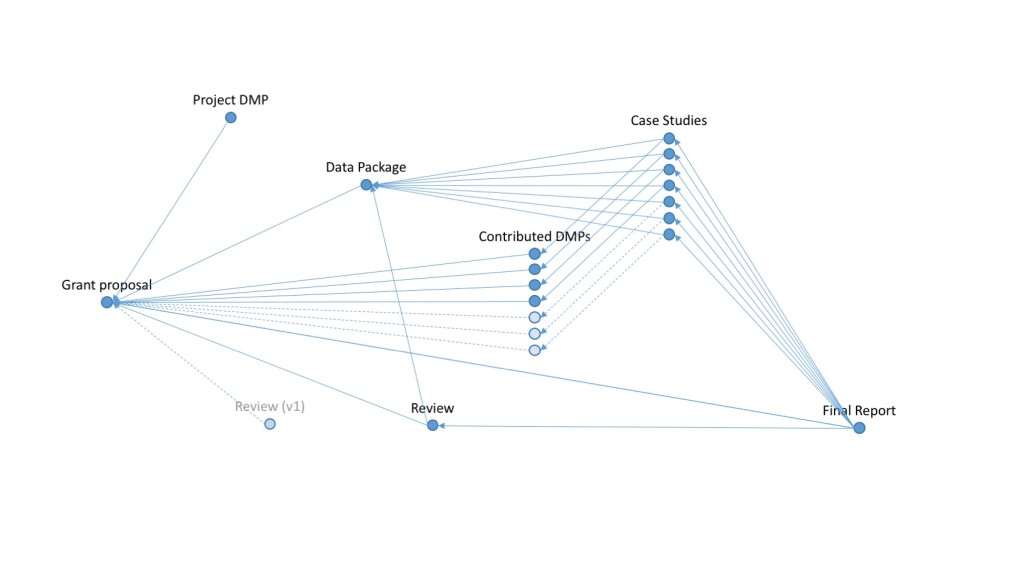

This leads to my key point of agreement with Lewis. The paper proposes a list of projects, approved for inclusion in the public reporting on investment. I would go further and develop an index of investment quality. The resources to support building this index would be the first project on the list. And members, having paid into that resource, get early and privileged access to the reporting, just as in investment markets. For any given project or service provider an assessment would be made on two main characteristics. How much of the money invested is re-circulated in the community? And an assessment of the quality of governance and management that the investment delivers, including the risk on the investment (high for early-stage projects, low for stable infrastructures)? Projects would get a rating, alongside an estimated percentage of investment that recirculates. Projects were all outputs get delivered with open licensing would get a high percentage (but not 100%, some will go in salaries and admin costs).

Commercial players are not excluded. They can contribute information on the resources that they circulate back to the community (perhaps money going to societies, but also contribution to shared infrastructures, work on standards, dataset contributions) that can be incorporated. And they may well claim that although the percentage is lower than some projects the services are better. Institutions can tension that, effectively setting a price on service quality, which will enhance competition. This requires more public reporting than commercial players are naturally inclined to provide, but equally it can be used as a signal of commitment to the community. One thing that might choose to do is contribute directly to the pool of capital, building shared resources that float all the boats. Funders could do the same, some already do by funding these projects, and that in turn could be reported.

The key to this, is that it can start small. A single library, funding an effort to examine the return it achieves on its own investment will see some modest benefits. A group working together will tell a story about how they are changing the landscape. This is already why efforts like Open Library of Humanites and Knowledge Unlatched and others work at all. Collective benefits would rise as the capital pool grew, even if investment was not directly coordinated, but simply a side effect of libraries funding various of these projects. Members gain exclusive benefits, access to information, identity as a leading group of libraries and institutions, and the prestige that comes with that in arguing internally for budgets and externally for other funding.

2.5% is both too ambitious and not ambitious enough

In the end I agree with the majority of the proposals in the 2.5% Commitment paper, I just disagree with the headline. I think the goal is over-amibitious. It requires too many universities to sign up, it takes political risks both internally and externally that are exactly the ones that have challenged open access implementation. It assumes power over budgets and implicit consent from academics that likely doesn’t exist, and will be near impossible to gain, and then hides it by choosing a small percentage. In turn that small percentage requires coordination across many institutions to achieve results, and as I argue in the paper, that seems unlikely to happen.

At the same time it is far from ambitious enough. If the goal is to shift investment in scholarly communications away from service contracts and content access to shared platforms, then locking in 2.5% as a target may doom us to failure. We don’t know what that figure should be, but I’d argue that it is clear that if we want to save money overall, it will be at least an order of magnitude high in percentage terms. What we need is a systemic optimisation that lets us reap the benefits of commercial provision, including external capital, quality of service, and competition, while progressively retaining more of the standards, platforms and interchange mechanisms in the community sphere. Shifting our thinking from purchasing to investment is one way to work towards that.