The Finch Report was commissioned by the UK Minister for Universities and Science to investigate possible routes for the UK to adopt Open Access for publicly funded research. The report was released last night and I have had just the chance to skim it over breakfast. These are just some first observations. Overall my impression is that the overall direction of travel is very positive but the detail shows some important missed opportunities.

The Good

The report comes out strongly in favour of Open Access to publicly funded research. Perhaps the core of this is found in the introduction [p5].

The principle that the results of research that has been publicly funded should be freely accessible in the public domain is a compelling one, and fundamentally unanswerable.

What follows this is a clear listing of other potential returns. On the cost side the report makes clear that in achieving open access through journal it is necessary that the first copy costs of publication be paid in some form and that appropriate mechanisms are in place to make that happen. This focus on Gold OA is a result in large part of the terms of reference for the report that placed retention of peer review at its heart. The other excellent aspect of the report is the detailed cost and economic modelling for multiple scenarios of UK Open Access adoption. These will be a valuable basis for discussion of managing the transition and how cost flows will change.

The bad

The report is maddeningly vague on the potential of repositories to play a major role in the transition to full open access. Throughout there is a focus on hybrid journals, a route which – with a few exceptions – appears to me to have failed to deliver any appreciable gains and simply allowed publishers to charge unjustified fee for very limited services. By comparison the repository offers an existing infrastructure that can deliver at relatively low marginal cost and will enable a dispassionate view of the additional value that publishers add. Because the value of peer review was baked into the report as an assumption this important issue gets lost but as I have noted before if publishers are adding value then repositories should pose no threat to them whatsoever.

The second issue I have with the report is that it fails to address the question of what Open Access is. The report does not seek to define open access. This is a difficult issue and I can appreciate a strict definition may be best avoided but the report does not raise the issues that such a definition would require and in this it misses an opportunity to lay out clearly the discussions required to make decisions on the critical issues of what is functionally required to realise the benefits laid out in the introduction. Thus in the end it is a report on increasing access but with no clear statement of what level of access is desirable or what the end target for this might look like.

This is most serious on the issue of licences for open access content which has been seriously fudged. Four key pieces of text from the report:

“…support for open access publication should be accompanied by policies to minimise restrictions on the rights of use and re-use, especially for non-commercial purposes, and on the ability to use the latest tools and services to organise and manipulate text and other content” [recommendations, p7]

“…[in a section on instituional and subject repositories]…But for subscription-based publishers, re-use rights may pose problems. Any requirement for them to use a Creative Commons ‘CC-BY’ licence, for example, would allow users to modify, build upon and distribute the licensed work, for commercial as well as non-commercial purposes, so long as the original authors were credited178. Publishers – and some researchers – are especially concerned about allowing commercial re-use. Medical journal publishers, who derive a considerable part of their revenues from the sale of reprints to pharmaceutical companies, could face significant loss of income. But more generally, commercial re-use would allow third parties to harvest published content from repositories and present them on new platforms that would compete with the original publisher.” [p87]

“…[from the summary on OA journals]…A particular advantage of open access journals is that publishers can afford to be more relaxed about rights of use and re-use.” [p92]

“…[from the summary on repositories]…But publishers have strong concerns about the possibility that funders might introduce further limits on the restrictions on access that they allow in their terms and conditions of grant. They believe that a reduction in the allowable embargo period to six months, especially if it were to be combined with a Creative Commons CC-BY licence that would allow commercial as well as non-commercial re-use, would represent a fundamental threat to the viability of their subscription-based journals.” [p96]

As far as I can tell the comment on page 92 is the only one that even suggests a requirement for CC-BY for open access through journals where the costs are paid. As a critical portion of the whole business model for full OA publishers it worried me that this is given almost a brief throw away line, when it is at the centre of the debate. But more widely a concern over a requirement for liberal licensing in the context of repositories appears to colour the whole discussion of licences in the report. There is, as far as I have been able to tell, no strong statement that where a fee is paid CC-BY should be required – and much that will enable incumbent subscription publishers to continue making claims that they provide “Open Access” under a variety of non-commercial licences satisfying no community definition of either “Open” nor “Open Access”.

But more critically this fudge risks failing to deliver on the minister’s brief, to support innovation and exploitation of UK research. This whole report is embedded in a government innovation strategy that places publicly funded knowledge creation at the heart of an effort to kick start the UK economy. Non-commercial licences can not deliver on this and we should avoid them at all costs. This whole discussion seems to revolve around protecting publishers rights to sell reprints, as though it made sense to legislate to protect candle makers from innovators threatening to put in an electric grid.

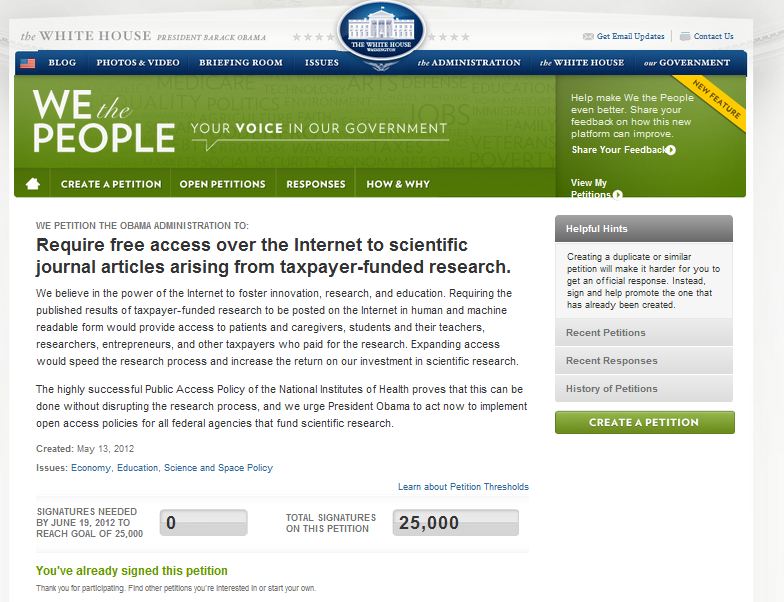

Much of this report is positive – and taken in the context of the RCUK draft policy there is a real opportunity to get this right. If we both make a concerted effort to utilise the potential of repositories as a transitional infrastructure, and if we get the licensing right, then the report maps out a credible route with the financial guidelines to make it through a transition. It also sends a strong signal to the White House and the European Commission, both currently considering policy statements on open access, that the UK is ready to move which will strengthen the hands of those arguing for strong policy.

This is a big step – and it heads in the right direction. The devil is in the details of implementation. But then it always is.

More will follow – particularly on the financial modelling – when I have a chance to digest more fully. This is a first pass draft based on a quick skim and I may modify this post if I discover I have made errors in my reading.

Related articles

Added Value: I do not think those words mean what you think they mean(cameronneylon.net)

Added Value: I do not think those words mean what you think they mean(cameronneylon.net)

U.K. Panel Backs Open Access for All Publicly Funded Research Papers(news.sciencemag.org)

U.K. Panel Backs Open Access for All Publicly Funded Research Papers(news.sciencemag.org)