This is a case of a comment that got so long (and so late) that it probably merited it’s own post. David Crotty and Paul (Ling-Fung Tang) note some important caveats in comments on my last post about the idea of the “web native” lab notebook. I probably went a bit strong in that post with the idea of pushing content onto outside specialist services in my effort to try to explain the logic of the lab notebook as a feed. David notes an important point about any third part service (do read the whole comment at the post):

Wouldn’t such an approach either:

1) require a lab to make a heavy investment in online infrastructure and support personnel, or

2) rely very heavily on outside service providers for access and retention of one’s own data? […]Any system that is going to see mass acceptance is going to have to give the user a great deal of control, and also provide complete and redundant levels of back-up of all content. If you’ve got data scattered all over a variety of services, and one goes down or out of business, does that mean having to revise all of those other services when/if the files are recovered?

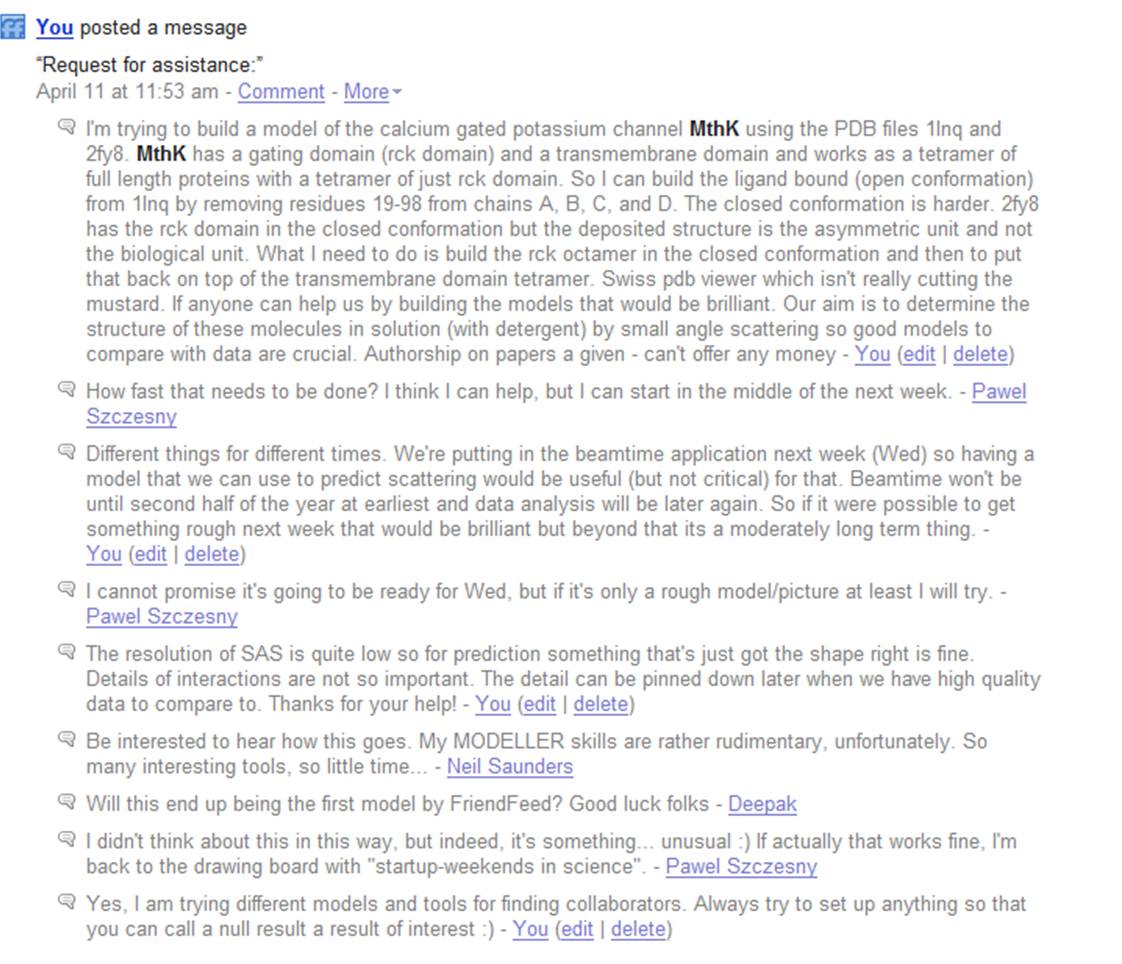

This is a very wide problem that I’ve also seen in the context of the UK web community that supports higher education (see for example Brian Kelly‘s risk assessment for use of third party web services). Is it smart, or even safe, to use third party services? The general question divides into two sections: is the service more or less reliable than you own hard drive or locally provided server capacity (technical reliability, or uptime); and what is the long term reliability of the service remaining viable (business/social model reliability). Flickr probably has higher availability than your local institutional IT services but there is no guarantee that it will still be there tomorrow. This is why data portability is very important. If you can’t get your data out, don’t put it in there in the first place.

In the context of my previous post these data services could be local, they could be provided by the local institution, or by a local funder, or they could even be a hard disk in the lab. People are free to make those choices and to find the best balance of reliability, cost, and maintenance that suits them. My suspicion is that after a degree of consolidation we will start to see institutions offering local data repositories as well as specialised services on the cloud that can provide more specialised and exciting functionality. Ideally these could all talk to each other so that multiple copies are held in these various services.

David says:

I would worry about putting something as valuable as my own data into the “cloud†[…]

I’d rather rely on an internally controlled system and not have to worry about the business model of Flickr or whether Google was going to pull the plug on a tool I regularly use. Perhaps the level to think on is that of a university, or company–could you set up a system for all labs within an institution that’s controlled (and heavily backed up) by that institution? Preferably something standardized to allow interaction between institutions.

Then again, given the experiences I’ve had with university IT departments, this might not be such a good approach after all.

Which I think encapsulates a lot of the debate. I actually have greater faith in Flickr keeping my pictures safe than my own hard disk. And more faith in both than insitutional repository systems that don’t currently provide good data functionality and that I don’t understand. But I wouldn’t trust either in isolation. The best situation is to have everything everywhere, using interchange standards to keep copies in different places; specialised services out on the cloud to provide functionality (not every institution will want to provide a visualisation service for XAFS data), IRs providing backup archival and server space for anything that doesn’t fit elsewhere, and ultimately still probably local hard disks for a lot of the short to medium term storage. My view is that the institution has the responsibility of aggregating, making available, and archiving the work if its staff, but I personally see this role as more harvester than service provider.

All of which will turn on the question of business models. If the data stores a local, what is the business model for archival? If they are institutional how much faith do you have that the institution won’t close them down. And if they are commercial or non-profit third parties, or even directly government funded service, does the economics make sense in the long term. We need a shift in science funding if we want to archive and manage data in the longer term. And with any market some services will rise and some will die. The money has to come from somewhere and ultimately that will always be the research funders. Until there is a stronger call from them for data preservation and the resources to back it up I don’t think we will see much interesting development. Some funders are pushing fairly hard in this direction so it will be interesting to see what develops. A lot will turn on who has the responsibility for ensuring data availability and sharing. The researcher? The institution? The funder?

In the end you get what you pay for. Always worth remembering that sometimes even things that are free at point of use aren’t worth the price you pay for them.