Over the past week this tweet was doing the rounds. I’m not sure where it comes from or precisely what its original context was, but it appeared in my feed from folks in various student analytics and big data crowds. The message I took was “measurement looks complicated until you pin it down”.

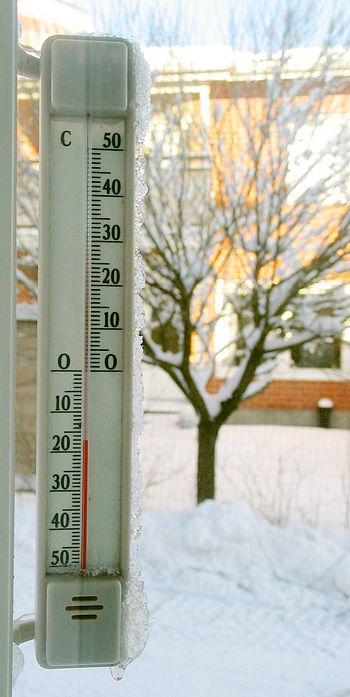

But what I took from this was something a bit different. Once upon a time the idea of temperature was a complex thing. It was subjective, people could reasonably disagree on whether today was hotter or colder than today. Note those differences between types of “cold” and “hot”; damp, dank, frosty, scalding, humid, prickly. This looks funny to us today because we can look at a digital readout and get a number. But what really happened is that our internal conception of what temperature is changed. What has actually happened is that a much richer and nuanced concept has been collapsed onto a single linear scale. To re-create that richness weather forecasters invent things like “wind chill” and “feels like” to capture different nuances but we have in fact lost something, the idea that different people respond differently to the same conditions.

Before thermometers: philosophers mocked the idea of temperature ever being measurable, with all its nuance, complexity and subjectivity pic.twitter.com/lPi1GfXWcr

— Siberian fox🔸 (@SilverVVulpes) April 7, 2017

Last year I did some work where I looked at the theoretical underpinnings for the meaning we give to referencing and citation indicators in the academy. What I found was something rather similar. Up until the 70s the idea of what made “quality” or “excellence” in research was much more contextual. The development of much better data sources, basically more reliable thermometers, for citation counting led to intense debates about whether this data had any connection to the qualities of research at all, let alone whether anything could be based on those numbers. The conception of research “quality” was much richer, including the idea that different people might have different responses.

In the 1970s and 80s something peculiar happens. This questioning of whether citations can represent the qualities of research disappears, to be replaced by the assumption that it does. A rear-guard action continues to question this, but it is based on the idea that people are doing many different things when they reference, not the idea that counting such things is fundamentally a questionable activity in and of itself. Suddenly citations became a “gold standard”, the linear scale against which everything was measured, and our ideas about the qualities of research became consequently impoverished.

At the same time it is hard to argue that a simple linear scale of defined temperature has created massive advances, we can track global weather against agreed standards, including how it is changing and quantify the effects of climate change. We can calibrate instruments against each other and control conditions in ways that allow everything from the safekeeping of drugs and vaccines to ensuring that our food is cooked to precisely the right degree. Of course on top of that we have to acknowledge that temperature actually isn’t as simple as concept as its made out to be as well. Definitions always break down somewhere.

And the concept of temperature still has subtleties:eg makes sense (mostly) just in equilibrium, has fluctuations etc. Also: lasers have T<0 https://t.co/LAo05cjMVQ

— Prof Stephen Serjeant 🇪🇺 @stephenserjeant (@StephenSerjeant) April 9, 2017

It seems to me that its important to note that these changes in meaning can affect the way we think and talk about things. Quantitative indicators can help us to share findings and analysis, to argue more effectively, most importantly to share claims and evidence in a way which is much more reliably useful. At the same time if we aren’t careful those indicators can change the very things that we think are important. It can change the underlying concept of what we are talking about.

Ludwig Fleck in The Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact explains this very effectively in terms of the history of the concept of “syphillis”. He explain how our modern conception (a disease with specific symptoms caused by an infection with a specific transmissible agent) would be totally incomprehensible to those who thought of disease in terms of how they were to be treated (in this case being classified as a disease treated with mercury). The concept itself being discussed changes when the words change.

None of this is of course news to people in Science and Technology Studies, history of science, or indeed much of the humanities. But for scientists it often seems to undermine our conception of what we’re doing. It doesn’t need to. But you need to be aware of the problem.

This ramble brought to you in part by a conversation with @dalcashdvinksy and @StephenSergeant

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=d8fea424-9fd4-40df-8e52-00e3e46a388b)