P ≠NP and the future of peer review

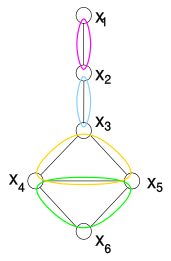

- Image via Wikipedia

“We demonstrate the separation of the complexity class NP from its subclass P. Throughout our proof, we observe that the ability to compute a property on structures in polynomial time is intimately related to the statistical notions of conditional independence and sufficient statistics. The presence of conditional independencies manifests in the form of economical parametrizations of the joint distribution of covariates. In order to apply this analysis to the space of solutions of random constraint satisfaction problems, we utilize and expand upon ideas from several fields spanning logic, statistics, graphical models, random ensembles, and statistical physics.”

Vinay Deolalikar [pdf]

No. I have no idea either, and the rest of the document just gets more confusing for a non-mathematician. Nonetheless the online maths community has lit up with excitement as this document, claiming to prove one of the major outstanding theorems in maths circulated. And in the process we are seeing online collaborative post publication peer review take off.

It has become easy to say that review of research after it has been published doesn’t work. Many examples have failed, or been partially successful. Most journals with commenting systems still get relatively few comments on the average paper. Open peer review tests have generally been judged a failure. And so we stick with traditional pre-publication peer review despite the lack of any credible evidence that it does anything except cost around a few billion pounds a year.

Yesterday, Bill Hooker, not exactly a nay-sayer when it comes to using the social web to make research more effective wrote:

“…when you get into “likes” etc, to me that’s post-publication review — in other words, a filter. I love the idea, but a glance at PLoS journals (and other experiments) will show that it hasn’t taken off: people just don’t interact with the research literature (yet?) in a way that makes social filtering effective.”

But actually the picture isn’t so negative. We are starting to see examples of post-publication peer review and see it radically out-perform traditional pre-publication peer review. The rapid demolition [1, 2, 3] of the JACS hydride oxidation paper last year (not least pointing out that the result wasn’t even novel) demonstrated the chemical blogosphere was more effective than peer review of one of the premiere chemistry journals. More recently 23andMe issued a detailed, and at least from an outside perspective devastating, peer review (with an attempt at replication!)Â of a widely reported Science paper describing the identification of genes associated with longevity. This followed detailed critiques from a number of online writers.

These, though were of published papers, demonstrating that a post-publication approach can work, but not showing it working for an “informally published” piece of research such as a a blog post or other online posting. In the case of this new mathematical proof, the author Vinay Deolalikar, apparently took the standard approach that one does in maths, sent a pre-print to a number of experts in the field for comments and criticisms. The paper is not in the ArXiv and was in fact made public by one of the email correspondents. The rumours then spread like wildfire, with widespread media reporting, and widespread online commentary.

Some of that commentary was expert and well informed. Firstly a series of posts appeared stating that the proof is “credible”. That is, that it was worth deeper consideration and the time of experts to look for holes. There appears a widespread skepticism that the proof will be correct, including a $200,000 bet from Scott Aaronson, but also a widespread view that it nonetheless is useful, that it will progress the field in a helpful way even if it is wrong.

After this first round, there have been summaries of the proof, and now the identification of potential issues is occurring (see RJLipton for a great summary). As far as I can tell these issues are potentially extremely subtle and will require the attention of the best domain experts to resolve. In a couple of cases these experts have already potentially “patched” the problem, adding their own expertise to contribute to the proof. And in the last couple of hours as Michael Nielsen pointed out to me there is the beginning of a more organised collaboration to check through the paper.

This is collaborative, and positive peer review, and it is happening at web scale. I suspect that there are relatively few experts in the area who aren’t spending some of their time on this problem this week. In the market for expert attention this proof is buying big, as it should be. An important problem is getting a good going over and being tested, possibly to destruction, in a much more efficient manner than could possibly be done by traditional peer review.

There are a number of objections to seeing this as a generalizable to other research problems and fields. Firstly, maths has a strong pre-publication communication and review structure which has been strengthened over the years by the success of the ArXiv. Moreover there is a culture of much higher standards of peer review in maths, review which can take years to complete. Both of these encourage circulation of drafts to a wider community than in most other disciplines, priming the community for distributed review to take place.

The other argument is that only high profile work will get this attention, only high profile work will get reviewed, at this level, possibly at all. Actually I think this is a good thing. Most papers are never cited, so why should they suck up the resource required to review them? Of those that are or aren’t published whether they are useful to someone, somewhere, is not something that can be determined by one or two reviewers. Whether they are useful to you is something that only you can decide. The only person competent to review which papers you should look at in detail is you. Sorry.

Many of us have argued for some time that post-publication peer review with little or no pre-publication review is the way forward. Many have argued against this on practical grounds that we simply can’t get it to happen, there is no motivation for people to review work that has already been published. What I think this proof, and the other stories of online review tell us is that these forms of review will grow of their own accord, particularly around work that is high profile. My hope is that this will start to create an ecosystem where this type of commenting and review is seen as valuable. That would be a more positive route than the other alternative, which seems to be a wholesale breakdown of the current system as the workloads rise too high and the willingness of people to contribute drops.

The argument always brought forward for peer review is that it improves papers. What interests me about the online activity around Deolalikar’s paper is that there is a positive attitude. By finding the problems, the proof can be improved, and new insights found, even if the overall claim is wrong. If we bring a positive attitude to making peer review work more effectively and efficiently then perhaps we can find a good route to improving the system for everyone.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Issues In The Proof That P≠NP (rjlipton.wordpress.com)

- Scott Aaronson adds $200K to prize money if P=NP proof correct (scottaaronson.com)

- HP Researcher Claims to Crack Compsci Complexity Conundrum (pcworld.com)

- S. Cook: “This appears to be a relatively serious claim to have solved P vs NP.” (gregbaker.ca)

- A Proof That P Is Not Equal To NP? (rjlipton.wordpress.com)

- R.J. Lipton – A proof that P is not equal to NP (rjlipton.wordpress.com)

- We need to fix peer review now (newscientist.com)

- Peer-review has a place (mndoci.com)

- Claimed Proof That P != NP (science.slashdot.org)

- Abundance Obsoletes Peer Review, so Drop It (opendotdotdot.blogspot.com)

- THE PROBLEM with peer review. “Especially for papers that rely on empirical work with painstakingly… (pajamasmedia.com)

I think that one reason the commenting and “likes” etc post-review process hasn’t taken off is that the infrastructure for making those comments is poor. As a researcher reviewing online, you would want a system that gives you credit for the work you are doing, also somewhere you can go to see all the comments and reviews you have made on different articles across different journals and blogs. You would want to be in control of those reviews. I have made a number of comments both on PLoS and Biomed Central but there is no way of me accessing, reviewing or deleting those comments I made and have never received any comments back from authors. If a system like DISQUS was set-up across different journals/publishers, you would have a way of being in control of the work you have done and be able to build a reputation in the research community by making reviews/comments and getting liked or disliked for it.

[…] P ≠NP and the future of peer review […]

Thank you for this post. I am as fascinated as you are by the process of peer review that has unfolded. It is the sort of phenomenon to restore my faith in human nature. I have been feeling warm and fuzzy for days because of it.

You have recognized that something very important is going on. I hope that others realize it as well. However, for anyone who wants to see this kind of thing happening more often, indeed to actively encourage it to happen more often, it is important to understand *why* it is happening. Yes, part of the reason is the extreme importance of the topic. Yes, part of the reason is that the Internet exists. But these are far from sufficient reasons. One only needs to consider what happened when the first million-dollar Millenium Prize problem was solved in 2003. That was a parallel situation, with a purported but incomplete proof distributed over the Internet only. In that case, however, the verification of the proof was fractured, prolonged, and bitter. Mathematicians don’t always cooperate this well. If you don’t know that story, you may read about it here: http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2006/08/28/060828fa_fact2

Let me add my hunch as to what happened differently in this case. I have seen collaborative phenomena such as the current one unfold in a few widely different contexts, as well as seen it die in infancy in many, many others. In my observation, the point of critical importance to whether teamwork happens or fails to happen is the quality of the moderator. I conjecture that it was no accident that the P=NP discussion crystallized around Dick Lipton’s blog as opposed to somewhere else, and furthermore that absent Dick Lipton, it wouldn’t have happened at all. Experts would have made scattered observations in various blogs and e-mails, collectively producing less in three weeks than the working group produced in three days.

Most such discussions are smothered in the cradle because the people whose contributions are most valuable choose not to contribute. The discussion isn’t killed internally, it dies from the best people staying away in droves. Their reasons for absence include fear of not being listened to, fear of being drowned out by idiots, expectation that the discussion will have no result, and fear of not being credited for their contributions if a positive result is produced. Yet anyone may rapidly verify from his blog that Lipton is generous with his own ideas, respectful of others’ ideas, fair-minded, competent to judge worthy from unworthy contributions, and eager to give credit where credit is due.

Like you, I would love to see the whole world work like the peer review of Deolalikar’s proof. To this end I believe we must understand it as a social phenomenon held together by the glue of an extraordinary individual. Lipton is exceptional not by virtue of being the most brilliant mathematical mind applied to the problem, but by having the rare social wisdom necessary to bring other great minds together.

I hope some sociologist picks up the ball for understanding such cooperative phenomenon better, because a society that comprehends it properly will be great above all societies.

I agree there are technical issues and usability issues with current commenting systems but even with good systems you see limited comments. There simply aren’t that many of us interacting with papers online. If you look at number of bookmarks in Citeulike/Mendeley or Delicious the numbers are pretty low. Most people land on the html, download the pdf, print and then annotate by hand. Nothing wrong with that, its a good workflow, but until we see more of the interaction happening in online spaces then the technical problems are relatively small.

Now someone did do a pubmed-Disqus mashup that looked really interesting, but I can’t find the link at the moment. Looked great, worked well, but are we using it? Even me?

Fritz, thanks for your thoughtful comment. I think you’re right on that there are two important characteristics here. One was the Deolalikar passed the initial “smell test” of credibility that meant serious people would take a look, and secondly as you say that Lipton was a key moderator. I’ve written before (tho not explicitly) about how we need to build social infrastructure that supports people like Lipton to mediate and support the application of expert attention. These people are “market makers” of a sort who provide the credibility that there is sufficient “capital” of attention to make a contribution worthwhile. These are very special people but they are often not held in high regard by people outside of their immediate circle.

In my mind I can imagine a sort of technical solution that provides a place where these people can mediate interactions at lots of different levels of specialisation and with different levels of reputation. We could probably build such a thing (indeed StackOverflow is arguably precisely such a thing for programmers) but it won’t work unless there is significant uptake and validation of the work of the mediators as an important contribution to the research community. So absolutely the key to this is understanding the sociology of this as a route to making it happen effectively more often.

Moving away from paper is indeed very difficult for scientists but I blame

the publishers. They make it harder for us by under investing in their

website infrastructure, not only in the tools available for commenting and

annotating but also with the lack of data available on their sites. Instead

of enriching the manuscripts we send them with the knowledge that is already

available on the web, they embed all the knowledge within a beautifully

formatted pdf that is too enticing not to print.

I’m hoping that tablets will change the way we work!

I agree that watching this happen has been wonderful. But I have no expectation that this method of reviewing will be practical in other fields, specifically biology. There aren’t very many mathematicians in the world who can work at this level. None of them have to worry about their contribution to the proof being overlooked. Mathematics is (at least in principle) provably true or false, not a matter of interpretation. There is little room for cherished beliefs, and no ability to argue that the evidence must be wrong because it contradicts your view, or that it really proves your own hypothesis. There is no pressure from the university you work for to patent first before you share your results, and no chance of someone with a larger lab jumping on your early findings and overtaking you — having a large group doesn’t actually help, in math. And mathematicians don’t have to worry about the NIH reviewers concluding that their work must be unimportant because it’s not published in the right journals. I am not arguing that the current state of peer review is good, just that there are reason to think that a transition to net review will not be easy.

Becky, you won’t get any argument from me on that. We know that this is hard and we certainly know that making a step change from one system to another won’t happen. Equally tho, some of these pressures are going to shift pretty quickly. The patenting thing is certainly shifting in some quarters as people realise just how few of those patents are making any money at all, and how many of them are just blocks to innovation and opportunities for patent trolls.

Even on the issue of grant review I think things are shifting. Bottom line, organisations that judges individual people on the basis of the journal’s they publish in (as opposed to the performance of their actual papers) need to take a long hard look at themselves because doing so is counterproductive and indeed highly non-scientific. You can’t actually predict anything about the quality of a paper (within reasonable error bounds) from the journal it appears in.

The broader question, could this work in biomedical sciences? Well I would say we have some examples, the Science GWAS paper I mention being one. Combine that with the current focus on “broader impact” and a re-calibration of what publication means and I think we will see a gradual change. It will take time – and it may only ever be applied to high profile work – but I think things are shifting away from where we were a few years back and that’s what I wanted to capture.

Absolutely! That’s partly what I was trying to argue here tho I’m not sure I made myself terribly clear. But I think as a community we need to take some responsibility for not demanding more as well. It’s part of the avoidance of responsibility that I feel derives from the fact that as researchers we make the decision about where to (try to) send our papers but we don’t have to deal with the cost, so we don’t squeal and demand good value for money.

I completely agree about the problems. (And yes, Bayh-Dole was enormously counterproductive). I hope you’re right that things are shifting. I don’t think what happened with the GWAS paper is as significant as you imply, though — essentially this was a debunking of a high-profile paper, which would have happened anyway, the Web just made it faster.

I used to be a journal editor and in that role I spent a lot of time trying to identify reviewers who met the following characteristics: not a direct competitor, but knowledgeable in the field. Willing to spend a significant amount of time giving a paper a serious evaluation as a service to the scientific community. Not so busy that it will take months to get the report. Has good judgment. These are not easy criteria to meet, and it isn’t hugely surprising if the system doesn’t work perfectly. On the other hand, I worked at it, and I got quite a lot of useful reviews that visibly improved the papers I dealt with. I know this is anecdotal evidence but I think it may be wrong to dismiss peer review as not useful. It is a hard thing to do well, though.

I guess the point for me about the GWAS paper is that the criticisms in the 23andMe post as well as comments by dgmacarthur (I think it was) and others revealed fundamental technical issues that should have been exposed by technical review at any reputable journal, let alone Science where one presumes the standard is somehow higher than average (I can’t speak to this myself as I’ve never reviewed for them nor had a paper get to review). It my be my reading of the post but it sounded as though there were fundamental technical checks that should be done for any GWAS paper that simply weren’t.

In terms of the editor’s problem, and I am an editor at PLoS ONE and for a new BMC journal soon to be launched, I couldn’t agree more. The question is whether its worth the bother, is it more effective to simply put it out for anyone interested to review, and then allow the paper to be iteratively improved in response to those comments until it reaches some sort of level of agreement that it gets some sort of quality mark. I would argue that those papers that don’t ever get a review should be released simply as data or blog posts or whatever. There will be some lost gems in there but that is a discovery problem – probably under the current system they wouldn’t be published anyway.

Don’t imagine that I’m saying peer review isn’t useful. But the question, is which peers, and when, and how do you motivate them to contribute positively to the process of improving this piece of communication?

I think it’s wrong to think of Science/Nature as aiming for a higher technical standard (or, at least, achieving it). They claim to distinguish themselves by two qualities, broad general interest and speed of publication. Speed is pretty much antithetical to highest possible technical review. One of the problems with the current situation, as you point out, is that the community has accepted “published in Science/Nature” as equivalent to “higher technical quality than the next paper”, which is not (necessarily) the case.

I do understand that what you’re talking about is substituting journal-driven peer review for community-driven peer review. My point is that peer review is real work, that substitutes for work you could be doing on your own papers, and it’s hard enough to get good peer review when you apply a good deal of skill and effort to obtaining it.

You express a hope that the kind of community-based commenting and review that happens in mathematics will be eventually seen as valuable. This would be great. It would help if such community service were seen as valuable by search committees and promotion committees. Could we create a website where “the best public peer review” gets aggregated and credited? Then you could put it on your CV and get some benefit out of it.

Absolutely agree with the need for credit. This is a fundamental of getting anyone to do anything, and is at the root of the many cultural problems in modern research. What I find interesting is that credit can seem trivial, people work hard to get high kudos on Stack Overflow or to get Facebook/Friendfeed “likes” or retweets. As these become important to people they can start to become “real” (Stack Overflow scores have appeared on some CVs for instance). To some extent I see these high profile examples of community review as starting to provide some legitimacy for those kind of contributions precisely because they have a high profile.

In terms of the “technical quality of review” question. I’ve certainly heard (but can’t lay my hands on any examples at the moment) CNS staff and editors say things like “the most rigorous peer review”, “always send to reviewers at least twice for detailed comments”, “often request extra experiments”. Again this is partly confusion over what peer review does and what its for but the brands of CNS are bound up with the idea that quality and stringency of review is higher here.

But at some level I’d also invoke the “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” rule. The examples I gave all made extraordinary claims. If peer review is going to do anything useful it must surely subject such claims to heavy duty scrutiny? I’m sure for every bad example exposed in a high profile journal there are many lower profile examples that never get picked up of course.

[…] to be considered, or only for the distant future, think again. Such open peer review has been happening in the sciences. Even in the Humanities, though, this is creeping in. Shakespeare Quarterly, for example, recently […]

[…] explanations why this is an important problem, and also that proofs are really, really hard. But as Cameron Neylon wrote, it was also a nice example of public peer review. A mere day after the announcement of the proof […]

License

I am also found at...

Tags

Recent posts

Recent Posts

Most Commented